INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains one of the main causes of preventable diseases including various types of cancers and coronary heart diseases1. Adolescents’ smoking remains one of the major public health concerns, since it is clearly found that onset of smoking in adolescence increases the chance of becoming a regular smoker in the future and reduces the chances of quitting later2.

Since the work of Evans et al.3 in the late 1970s, it is clear that social factors are strongly related to smoking onset in adolescents, particularly pressure exerted by others, mostly peers, parents and the mass media. School-based smoking prevention programs using a social influence approach in which youngsters learn how to cope with these pressures were found to be significantly effective although program effects decay after a couple of years4,5. Studies suggested that program effectiveness could be enhanced when using interactive delivery methods and involving adolescents as group leaders2,6,7. Adaptation of the social influence approach to other countries requires that one verifies whether similar determinants operate as those found in industrialized parts of the world, such as the US and Europe. Research in non-western countries revealed that similar constructs as those found in western countries are relevant: attitudes, social influences and self-efficacy8,9, but that the content of these factors may be determined by specific variables within such a culture. Hence, it is vital to identify the most important determinants of smoking behaviour before developing a program.

Investigating determinants of behaviour and identifying preferences of the target group of educational strategies to be used is an important step in program development, where using qualitative methods can yield rich and in-depth information10,11. Consequently, qualitative research has been widely used by researchers to explore the views of adolescents about certain behaviour, for instance: smoking12, nutritional habits13 and sexual behaviour14,15.

As reported by various studies overall smoking prevalence in Saudi Arabia ranges from 12% to 29.8%16. Among adolescents, as documented in a recent review including 32 studies, the reported prevalence was somewhat higher than among other age groups, whereas prevalence among boys was higher than among girls (12.4–39.6% versus 3.8–11.1%, respectively)17. Yet, most of these studies mainly reported smoking prevalence and did not target its determinants, such as attitudes, social factors and self-efficacy; those that did address determinants of smoking18-20 revealed that friends, parents and important other people, have the most effect on youngsters.

The first goal of this study is to explore the determinants of adolescents’ smoking behaviour and to explore potential differences between smokers and non-smokers. A second goal is to explore adolescents’ preferences for intervention development and implementation of smoking prevention programs. Perceptions of both adolescents living in rural and urban areas were assessed to identify potential differences as well.

METHODS

This is a qualitative study among 103 school-going adolescents, from nine schools in Saudi Arabia, who were interviewed in 11 focus group discussions. Ethical clearance in the region of the study was only granted for interviews with male adolescents, as authorities indicated that smoking was not allowed among females. Smokers and non-smokers were separately interviewed: smokers in five groups, and non-smokers in six groups. Two researchers supervised each of the 11 focus groups: one led the discussion and took notes, while the other was in charge of audio-visual recording. All the discussion groups were held during schooldays in the school library and out-of-class time. The group discussions were held in absence of teachers and parents in order to let the participants talk and express themselves freely. All the group discussions were recorded. Each group was attended by 9–11 participants, the discussion for each group took 45–55 minutes (the normal class in Saudi Arabia is 45 minutes), smokers’ groups were more active than those of the non-smokers, rural boys were less active than the urban boys, yet almost all participated in the discussion.

Participants

We approached 120 adolescents who were purposely selected, 60 adolescents from each group (smokers and non-smokers), 17 refused to participate (ten smokers and seven non-smokers), those who agreed to participate were 103 (85.8%), from nine randomly selected schools, six were urban schools and three were rural schools from Taif province in Saudi Arabia. Fifty adolescents were smokers and fiftythree were non-smokers (Table 1). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the provincial school management structure, which involved the Director General of education in Taif province, the director of the school health program as well as the principals of the nine participating schools. A written justification of the study was provided to the parents of all the 103 students and their written consents obtained. Verbal consents of participants were obtained after explaining to them the study goals and giving the chance not to participate or to stop whenever they wished.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of participating school-going adolescents, Saudi Arabia

Procedure and topic guide

For data collection, we developed and used a discussion guide based on the I-Change Model21 , a model that integrates concepts from various social cognitive theories, and which was used to study smoking behaviour in Europe22 and the Middle East9. The discussion guide addressed the following factors: advantages and disadvantages of smoking attitude, social-influences in favour or against smoking, situations that make it difficult not to smoke (selfefficacy) and what to do about this (action plans), and intention to smoke (Table 2). Participants were also given the chance to raise additional topics during the interviews and address any factors related to their smoking behaviour other than those included in the guide. Questions were then raised to assess preferences for a smoking prevention program; content (what should be discussed and how, e.g. using scary messages or scientific information), timing (during school time or out-of-school time), place inside the school (classroom, library or other) or outside the school. Method of delivery (electronic, printed materials, role-play or other) and channel of delivery (teachers, school health staff, peers or others). Additionally, we assessed age, smoking status (defined as having smoked at least one cigarette in the last day/week/month). Smokers and non-smokers addressed the same factors, and questions were adapted to best match their smoking status.

Table 2

Questions asked and item discussed with school-going adolescents, Saudi Arabia

Data analysis

The video recorded interview data and the written notes were revised by the research team. Based on the group discussion questions and answers, a coding scheme was developed by the principal researcher and research assistants. The transcripts were then coded, using QDA Miner (v2.0), a qualitative data mining and visualisation tool23. We performed the coding following the thematic coding approach provided by the software, we organized the texts into three levels: 1) demographic factors, age, grade and area (urban, rural); 2) smoking status (smokers and non-smokers); and 3) smoking determinants (attitude, self-efficacy, social influence, and intention). During the coding procedure, additional sub-codes were added to the coding scheme for the items that did not belong to any of the above three levels. To check the validity of the coding process, two transcripts were fully coded by the principal researcher and one of the research assistants, and to avoid bias a third person checked the coding results. The most frequently mentioned items per factor were grouped under headings if they represented similar types of answers.

RESULTS

Participants

The sample included 103 male adolescents aged 12–16 years with mean age of 13.8 years, with 29 (28.2%) in grade seven, 43 (41.7%) in grade 8, and 31 (30.1%) in grade nine. Non-smokers were 53 (51.5%) and smokers were 50 (48.5%). Of the total sample, 37 (35.9%) were from rural areas and 66 (64.1%) from urban areas (Table 1).

Perceived smoking determinants

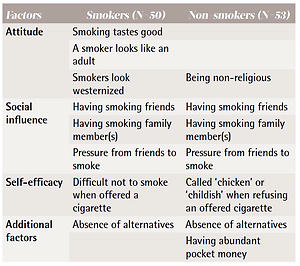

Attitude

Concerning the perceived advantages and disadvantages of smoking, several consequences were mentioned, and smoking boys clearly differed on several beliefs from non-smokers. Table 3 gives the main differences between the two groups. All smokers stated that people of their age smoke to prove that they are adult and mature. This belief was held by most urban and rural smokers and by most rural nonsmokers. In contrast, urban non-smokers expressed that being a smoker does not make them feel more civilized or western.

Table 3

Summary for the most frequently mentioned factors to smoke for school-going adolescents, Saudi Arabia

‘Look my friend; when I smoke, then I am a real man, an adult not a kid any more, even other see me as a man, a civilized man.’ (Rural smoker, grade seven, 13 years)

‘Being a smoker, having a cigarette, cigar or even smoking pipe, will not make you civilised or western.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

Smokers from both areas mentioned that most of them smoke because of its good taste.

‘The right question is why didn’t non-smokers start to smoke, it is tasty and you will never know that unless you taste it.’ (Urban smoker, grade eight, 14 years)

All non-smokers from the two areas think that people of their age smoke because they underestimate the harmful effects of cigarettes on health.

‘They don’t look to the consequences of smoking; they think it doesn’t affect their health, but smoking does.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade seven, 13 years)

‘Most probably they don’t know that it only kills them, if not; they will be sick, and what a nasty smell it gives to the breath.’ (Rural non-smoker, grade seven, 14 years)

Smokers from the two areas were not convinced that smoking is harmful to their health.

‘I don't think it has effects on my health. My 65-year-old grandfather has been smoking for the last 40 years: he is still healthy. It has nothing to do with health.’ (Rural smoker, grade eight, 14 years)

‘In the media, doctors always warn us about the hazards of smoking; look to my grandfather, who is now over 75 years old and being smoker for more than 50 years and he is quite well. I don't think smoking is bad for my health.’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

Most of non-smokers stated that being a smoker implies being non-religious and that for them this was one of the reasons not to smoke.

‘The devil always likes making people do the bad and wrong things, if you are not religious enough you are going to follow and smoke.’ (Rural nonsmoker, grade eight, 13 years)

Social influences

Smokers and non-smokers differed concerning the norms that they encountered with smoking, the amount of smoking (male) adults, and in particular smoking pressures from friends, the father, older brothers, and older cousins and uncles. All smokers from rural and urban areas, but less non-smoking adolescents, mentioned to have at least one family member or a friend who smokes. One participant stated, pointing to one of the participants in the group and laughing:

‘He is the boy who introduced me to smoking. He offered me a cigarette, which I could not refuse, the next day I bought the third cigarette stick myself. And here I am, friends being alike.’ (Urban smoker, grade seven, 12 years)

Almost all non-smokers agreed on the influence of the father, older brothers and cousins on adolescent smoking behaviour, as they serve as role models for what is the norm in smoking.

‘Like father like son, when your father smokes, this means the right thing to do is to smoke.’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 14 years)

‘If your father and your elder brother(s) smoke, why wouldn’t you?’ (Rural non-smoker, grade seven, 12 years)

Self-efficacy

Smokers and non-smokers differed concerning situations where it was difficult not to smoke. Smokers appeared to often have friends that also smoke. Consequently, smokers mentioned that it would be very difficult not to smoke in these social situations when a friend would offer a cigarette or when in a group of smoking friends.

‘Even if you don’t want to smoke at some moment, it is not easy to refuse an offered cigarette from your buddy, it is nice to share smoking with a friend.’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

Non-smokers found it difficult not to smoke, especially when they were going to be called childish by others if they refuse an offered cigarette.

‘I can't accept to be called ‘chicken’ or ‘still a child not a man’, if I didn’t smoke an offered cigarette, so I have to take it.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade nine, 14 years)

Being at risk to smoke was also mentioned by most non-smokers when having more pocket money, as they mentioned, smoking would then become very easy to do. Additionally, smokers mentioned that feeling bored also increased the risk to smoke, in particular in the absence of alternatives like entertainment places. In Saudi Arabia bachelors are not allowed to visit shopping malls, thus reducing possibilities for finding entertainment.

‘Look at our area, there are buildings everywhere, no place for sport activities. Sport clubs are expensive and malls are for families only. The easiest thing to do is to smoke, it doesn't cost much.’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 14 years)

Intentions

Both groups mentioned that intention and will power are important to practice or not to practice smoking. Few smokers had the intention to quit smoking, but several non-smokers were intending not to start smoking.

‘It is also the will and intention, if you want to smoke you will. If not, you won't.’ (Rural nonsmoker, grade nine, 13 years)

Action plans

Most smokers and non-smokers did not mention a wide array of action plans to prepare them not to smoke or how to deal with challenging situations that may prompt them to smoke. Almost all non-smoking participants mentioned that having non-smoking friends would help them to continue being a non-smoker.

‘Having good friends, doing the right things, helped me a lot not to start smoking; I prefer to be with them my whole life.’ (Rural non-smoker, grade eight, 13 years)

Both non-smokers and smokers mentioned the need for having good strategies to being able to refuse cigarettes.

‘Although it is hard to refuse an offered cigarette, if only we learned how to say “No” in such situations we wouldn’t be smokers.’ (Rural smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

The main reasons considered for smoking were: having a family member or a friend who smokes, lack of alternative pastime, availability and affordability of cigarettes, denial of smoking effects on health, and smoking being tasty. Non-smokers agreed with smokers in having pocket money being a reason to smoke. Additionally, non-smokers see that being unreligious is one of the reasons to smoke and some of them see that being a smoker is a way to be non-religious. All participants thought that being busy with useful activities is protective from starting smoking. The two groups agreed on having non-smoking friends and having alternative pastime may be protective against smoking behaviour, but the two groups had contradictory views on the value of information about smoking effects on health (Table 3).

Intervention program preferences

Contents of the intervention program

When asking about the content of a smoking prevention program, the need for learning refusal skills and learning more about health were mentioned as the core topics. For an eeffective smoking prevention program, participants from the smoking and non-smoking groups both suggest an intervention that helps to say no to cigarettes and how to cope with others’ pressure to smoke.

‘If I had known how to say no to the first cigarettes offered to me, I would not have started smoking. As such, I think it is better for teenagers like me to be taught early enough how to say no. That is the entire story.’ (Urban smoker, grade eight, 13 years)

Additionally, smokers and non-smokers indicated the need for stressing the importance of health, the detrimental effects of smoking to their health at short-term, and provide alternatives to feeling bored.

‘I think the program should concentrate on physical fitness. Everybody now wants to be a good player in football, basketball or whatever. If they knew that smoking would make their hopes go with the wind, they wouldn't smoke.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

Besides giving information about the impact of smoking on health, respondents also indicated that the program should include getting the target population to visit smokers hospitalized due to the adverse effects of smoking.

‘This is the better way [visiting hospitalized smokers]. People are usually afraid of diseases and death. With this, the smokers will perceive their dark future and then quit and non-smokers will not start smoking.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade eight, 14 years)

Channel of intervention program delivery

We asked the adolescents who should be teaching the program, such as teachers and religious leaders. Only few of the participants agreed that a teacher would be an appropriate intervention provider as most of them smoke themselves.

‘When somebody tells people not to practice a certain behaviour, while he is practicing it, it is a shame to do that. Most of the teachers (if not all) smoke, so they aren't the right persons to tell others not to start smoking.’ (Urban non-smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

Almost none of the participants regarded a religious man as suitable; mostly due to their perception that Imams preach and adolescents usually do not like to listen to a sermon. Almost all participants preferred to have a program that combines a delivery by the school health staff with active participants’ involvement.

‘The school health staff is suitable for this job, they know what they are doing, and they consider what we want. Then such a program is a good example for their work.’ (Rural non-smoker, grade eight, 13 years)

Format of the intervention program

Additionally, we explored how the program should look like concerning the format and the timing of program delivery. None of the participants believed providing a program with only printed materials like brochures and pamphlets would be attractive and effective. Almost all rejected the idea of lectures.

‘Lectures are boring. We have had enough lectures during the school classes, we just sit to listen because we have to, we aren't really listening; it is as if we weren’t there. Some of us even fall asleep during the lectures.’ (Rural non-smoker, grade seven, 12 years)

Almost all of the participants suggested to use role plays and movies as forms of intervention delivery.

‘Why not do something that gives us the sense of responsibility and ownership? Something that tells us that we are a part of it, like a movie we make or a role play and we are the players or group work and leaders. For how long are we going to be listeners?’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 14 years)

Timing of the intervention program

All participants agreed upon timing to be during the school day.

‘Nobody will come to attend a program in his free time. It is time for fun and not for activities that make you remember the lessons. If the program is going to be a matter of fun and during school time, then it is ok.’ (Urban smoker, grade nine, 15 years)

In summary, Saudi adolescents prefer to have an interactive smoking prevention program, with refusal skills provided via role-play, drama and group discussion, delivered during school time by healthcare workers and group work led by peers (Table 4).

Table 4

Summary of the intervention program components suggested by 103 school-going adolescents, Saudi Arabia

DISCUSSION

This study explored male adolescent’s perceptions on smoking behaviour and its determinants, as well as their views on the content and format of a smoking prevention program. From the data, it is clear that one of the driving factors for adolescents to start smoking concerns a positive attitude and positive outcomes associated with smoking. In particular, positive outcomes such as smoking is tasty, helps you to show off and to be seen as an adult, were clearly mentioned by smoking participants, which is consistent with other studies24. To be seen as western was also regarded as important, both among smokers, but also among rural non-smokers. It is conceivable that this belief can be also the result of influences of television, movies and other media25. Furthermore, some beliefs served to prevent smoking, such as being convinced of the detrimental health effects, and the fact that smoking is not in line with religious beliefs. This finding is in line with other studies in Saudi Arabia that found religion to be an important reason for not smoking among non-smokers26-28.

Social influences such as modelling, norms and social pressure were mentioned to be main causes for adolescents to start smoking. In particular, the father, older brothers and cousins, and smoking friends were clearly mentioned. The influence of friends is also reported in other international studies investigating smoking behaviour determinants among adolescents29. Yet, in contrast to western cultures, the role of fathers, older brothers, cousins and uncles may be more salient in the Saudi Arabic culture, where relatives of the same gender play a very important role and where it is important to behave similar to older males17,20. Additionally, compared to boys in modern western societies, Saudi boys are not as strictly supervised as girls, and use of tobacco is regarded as a means of obtaining and preserving a masculine image and maturity among peers20.

In line with international studies22,30,31, we also found that low self-efficacy to refrain from smoking was an important risk factor for adolescents to start smoking. Smoking Saudi boys mentioned that they lacked skills to refuse offers for smoking a cigarette, and mentioned, as did non-smokers, that this should be addressed in a smoking prevention program. Additionally, non-smokers often mentioned that they were called cowards and not grown-up or not western, highlighting a need for non-smoking youngsters to be made able and confident to address these issues. These were also mentioned when discussing which action plans were needed. In line with other studies addressing this issue32, our interviews revealed also that having non-smoking friends, how to cope with boredom also needed to be addressed in a smoking prevention program. As part of community regulations in Saudi Arabia, bachelors are not allowed to visit shopping malls, thus reducing possibilities for entertainment. Furthermore, the available gym and sport centres are not affordable by them. Consequently, adolescents are confronted with modest possibilities to entertain themselves. Modifications in these policies may thus be needed in order to prevent adolescents to entertain themselves with smoking, which is moderately cheap and easily accessible.

For the development and implementation of an anti-smoking intervention program, participants suggested to include a hospital visit to see those who were badly affected by smoking. Yet, although mentioned, this suggestion is contradictory to what is found in the literature about fear appeals, showing that coping appraisals are more powerful predictors of precautionary action than threat perceptions33. Because of the traditional method followed in Saudi Arabia for teaching (i.e. delivering lectures to the class), adolescents dismissed a similar method as this was regarded as boring and unattractive. Alternatively, they suggested a new approach in which they should be part of the program delivery and not only listeners. They argued for healthcare workers as program providers, and peer-led group discussions. These suggestions are consistent with peer-led approaches described by others and in line with conditions for effective school based intervention programs with long-term expected effects7,34. Adolescents again stressed the need be trained on how to cope with pressure in line with recent reviews that revealed that peer-led programs are effective when combined with social competence/social influences curricula35. The best timing chosen by participants for the program activities would be during school days within the school setting, since the school setting offers a homogenous environment with availability of students in the school time36.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first qualitative study that explores the determinants of smoking behaviour among Saudi male adolescents, hence the selected participants were enthusiastic to participate. Using the I-Change Model as a theoretical framework enhanced the exploration of the smoking determinants. The structured interview guide with the open-ended questions helped the participants to express their opinions without limitations. The interviews in absence of teachers and parents helped students to talk freely.

In our study only school-going male adolescents were interviewed, and we were not able to include female adolescents. Hence, the findings of our study are limited to the group interviewed and cannot be generalised. Given the fact that smoking uptake is becoming more popular in recent years among groups that were not represented by the sample, more research to investigate these groups is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

The study reveals established important factors related to smoking onset, but also the importance of specific cultural beliefs within these factors to be addressed, such as the importance of looking western as a driver for smoking and adhering to Islam as a preventive factor. For male boys, the smoking male context provides enormous social challenges in order not to start smoking, indicating the importance to focus on these items when increasing self-efficacy not to smoke and to develop specific action plans for these situations. This also suggests a clear need not only to target male adolescents but also male adults in order to change social norms about smoking. Lastly, the respondents in our study preferred an interactive school prevention program in which they could play an important role with the guide of peer leaders.