INTRODUCTION

Smoking is a major worldwide health problem that has serious impact on individuals and public health. In the US, smoking causes more deaths every year than the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), illegal drug use, motor vehicle injuries and firearm-related incidents1. Smoking causes about 90% of all lung cancer deaths and about 80% of all deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)2. According to the World Health Organization’s 2013 standardized estimate of smoking prevalence, 40.5% of men, 0.3% of women, and 20.3% of Egypt’s population overall, are daily tobacco smokers. Because of limited agents for smoking cessation, research is being conducted on the available drugs used. One of these is topiramate. Topiramate is an antiepileptic drug used for many indications such as epilepsy3, mood stabilization4, eating disorders5 and migraine prophylaxis6. Studies have been increasing regarding topiramate use for various addictions such as cocaine, alcohol and cannabis7-9. A few clinical trials have been conducted on the effect of topiramate on smoking cessation but they did not have enough power to show superiority of topiramate over the placebo, although some studies showed a numerical difference. Thus, a meta-analysis is required to get more power and clarify the true effect of the drug. The objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of topiramate in assisting smoking cessation.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

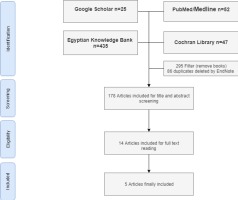

A comprehensive internet search was conducted in March 2019 using the following databases: PubMed/Medline, Cochrane, Egyptian Knowledge Bank, and Google Scholar. There were no restrictions regarding language or publication date. A Boolean search was conducted using the following search string: [topiramate] AND [smok* OR cigarettes OR tobacco]. The search was adjusted to suit each of the chosen search engines and databases. Once the search was completed, duplications were removed and we elected to include only clinical trials that examined the effect of oral topiramate compared with the placebo on smoking cessation rates in adult smokers. Two of the authors (HE and NL) screened all articles obtained from the search, based on title and abstract, to get all relevant articles for full-text consideration. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Definition of outcomes

Data extraction

Data from each study were extracted independently by two authors (HE and NL) regarding the following: study methodology, sample size, type of the population, topiramate dose and duration, comparators, time and setting of the study. Additionally, smoking abstinence rate as a point or period prevalence was extracted.

Clinical trial quality assessment

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 check-list was used to assess the quality of clinical trials10.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias was used for the included studies11. This tool consists of seven domains: sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) and other potential sources of bias. It was assessed independently by two authors (HE and NL).

Statistical methods

Considering the prolonged (4-week) smoking abstinence rate, the number of smokers that quit smoking was extracted from each study, while the point smoking abstinence rate was extracted from graphs using the specific software ‘GetData Graph Digitizer’ and then an all time-points meta-analysis (ATM)12 was conducted to assess evidence at every time-point reported by the included studies. The overall effect size pooled OR was estimated using a Mantel-Haenszel fixed effect method, with 95% confidence intervals, and heterogeneity test using the Q statistic. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding the low-quality studies. Due to the small number of included studies, the publication bias and subgroup analysis could not be conducted. The analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.3.

RESULTS

Search results

A total of 178 studies were identified from the search, after duplication removal. After title and abstract screening, 164 studies were removed, and the remaining 14 studies were assessed for eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Only 5 studies were eligible for systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the reasons for exclusion of some articles in the final stage.

Table 1

Excluded studies and reasons

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Weinberger et al. 200831 | Abstinence rate was not reported. Only CO level was reported |

| Vaughan et al. 201432 | The intervention was topiramate with amphetamine salt |

| Baltieri et al. 200928 | Abstinence rate was not reported, number of cigarettes was reported instead |

| Campayo et al. 200833 | The outcomes were not reported |

| Reid et al. 200734 | Nicotine withdrawal symptoms were measured |

| Worley et al. 201830 | Smoking abstinence rate was not reported, number of cigarettes was reported instead |

| Sofuoglu et al. 200635 | Topiramate was used with IV nicotine |

| Isgro et al. 201529 | Abstinence rate was not reported. Number of cigarettes was reported instead |

| Khazaal et al. 200636 | No control group was used |

Characteristics of included studies

The five included studies involved 447 participants at baseline, 220 for topiramate treatment, and 227 as control. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 70 years and the majority of participants were males recruited from the community. Topiramate was used orally with an initial small dose, titrated gradually up to 300 mg/day, except for one study13 that started with 200 mg/day and stopped gradually. The duration of topiramate ranged from 8 to 12 weeks. Carbon monoxide confirmation for smoking abstinence was done in 3 studies, while in the other 2 studies the abstinence was based on self-reporting13,14. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Methods | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Topiramate | Control | Prolonged AR | Point AR | |||

| Anthenelli et al. 2017*15 | Randomized control study, double blind, parallel group | 129 alcohol-dependent male smokers, aged 18–70 years | 12-week clinical trial | 63 participants taking topiramate up to 200 mg daily divided into doses: first in 25 mg increments (weeks 1–4) and then in 50 mg increments (weeks 5–6) | 66 participants taking placebo orally | Biochemically confirmed 4-week continuous abstinence from smoking during weeks 9–12 | 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence rates during treatment (weeks 6–12) |

| Oncken et al. 201417 | Randomized control study, double blind | 57 participants who smoked at least 10 cigarettes/day during the past year | 10-week clinical trial | 19 participants started at the baseline visit and the dosage was titrated up over 5 weeks (25 mg/day for 1 week, 25 mg twice daily for 1 week, 50 mg twice daily for 1 week, 75 mg twice daily for 1 week, and 100 mg twice daily for 5 weeks) | 19 participants taking placebo orally | The last 4-week continuous abstinence rates and CO-confirmed | Weekly abstinence rates, 7-day point prevalence confirmed by exhaled CO ≤10 ppm, by treatment weeks 2–10 |

| Johnson et al. 200514 | Randomized control trial, double blind | 94 alcohol dependent who reported smoking ≥1 cigarettes/day, aged 21–65 years | 12-week clinical trial | 45 participants taking topiramate up to 300 mg daily divided into doses, first in 25 mg increments (weeks 1–4), and then in 50 mg increments (weeks 5–8) | 49 participants taking placebo orally | Weekly self-reported cigarette smoking at weeks 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12 | |

| Anthenelli et al. 200816 | Randomized control trial, double blind | 77 chronic smokers who smoked on average >10 cigarettes/day | 11-week clinical trial | 43 topiramate up to a maximum dose of 200 mg daily in twice-daily divided doses. Topiramate was started at 25 mg, taken at bedtime, and increased by 25 mg/day each week (weeks 1–4) or 50 mg/day each week during weeks 5 and 6 until 200 mg/day was reached at week 6 | 44 participants taking placebo orally | Carbon monoxide confirmed 4-week prolonged abstinence rate during weeks 8–11 | |

| Liang et al. 2008**13 | Non-randomized control trial | 99 patients with depression | 12-week clinical trial | 50 participants taking topiramate 200 mg/day from weeks 1–4, and then decreased progressively from the 5th week, and finally discontinued at the end of the 8th week | 49 participants taking placebo orally | Quit success rate, ≤1 cigarettes/day considered as a successful quit, for weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 and 12 | |

Risk of bias among the included studies

Random sequence generation, performance and detection bias were low in all studies, except for one study13. On the other hand, the allocation concealment presented an unclear risk of bias among all studies, except for one study15. Regarding attrition bias, there was an unclear risk of bias in one study16, while the remaining showed low risk. More details are presented in the Supplementary file.

Outcomes

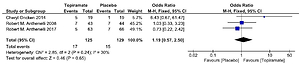

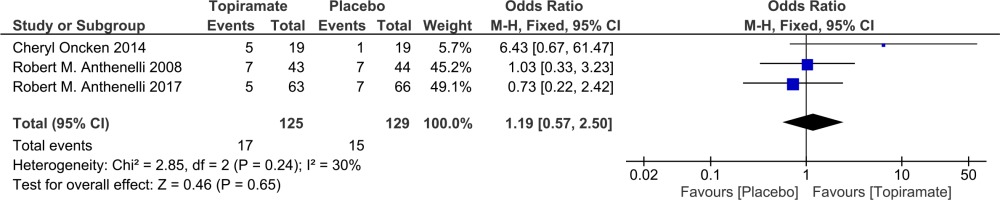

Four studies were used to assess point smoking abstinence rate13-15,17 and three studies were used to assess the prolonged (4-week) smoking abstinence rate15-17. None of the three studies achieved a statistically significant effect for topiramate compared with the placebo. Combining the results of the three studies (Figure 2) provides a pooled odds ratio (OR=1.19, 95% CI: 0.57–2.5) implying that smokers who were given topiramate had no significantly higher rates on 4-week abstinence from smoking than for the placebo. The Q statistic did not show significant heterogeneity (χ2=2.85; p=0.240; I2=30%).

Point smoking abstinence rate outcome

It was found that the pooled odds ratios of smoking abstinence in the topiramate-treated group at weeks 4, 6, 8 and 12 were significant (OR=3.07, 95% CI: 1.19–7.93; OR=4.03, 95% CI: 1.98–8.2; OR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.23–4.28; OR=2.45, 95% CI: 1.37–4.39; respectively) compared with the control (Figure 3). On the other hand, the pooled odds ratios at weeks 2, 3, 7, 9 and 10 were not significant (OR=1.42, 95% CI: 0.43–4.73; OR=1.46, 95% CI: 0.48–4.45; OR=2.37, 95% CI: 0.81–6.98; OR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.72–2.73; OR=1.29, 95% CI: 0.61–2.73; respectively). The Q statistic did not show significant heterogeneity for any of the time points.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding the low-quality study13 and it was found that the pooled odds ratio of topiramate had a statistically significant effect at week 6 (OR=2.93, CI: 1.08–7.91). The Q statistic did not show significant heterogeneity for any of the time points (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Smoking is a worldwide health problem and many efforts have been made to reduce it. Only three pharmacotherapies are approved by the FDA for smoking cessation: nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion18 and varenicline19. Other medications that are not FDA-approved but which showed efficacy in clinical trials are nortriptyline20 and clonidine21. Behavioral therapy in combination with pharmacotherapy increases the smoking quit rate compared with pharmacotherapy alone22. The recommended first-line for smoking cessation by the American College of Cardiology is varenicline or a combination of nicotine replacement therapy; the second-line is topiramate, a well-tolerated antiepileptic drug23,24 that has shown some benefits in smoking cessation in a few clinical trials. The question is, however, what are the reliable measures for effectiveness of a treatment to enhance smoking cessation and for how long? An ongoing clinical trial is comparing varenicline and bupropion25. The primary outcome is smoking prevalence and continuous smoking abstinence, biochemically confirmed by salivary cotinine after 4, 8, 12, 26 and 52 weeks of starting a 12-week treatment. A new meta-analysis examined efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in schizophrenia25. The outcome measures were: number of cigarettes and CO level over the treatment period up to 3 months. A recent trial measured the abstinence rate after 12 months of starting varenicline treatment26. In the present meta-analysis, the reported prolonged abstinence rates were measured during the last 4 weeks of starting the treatment, which may underestimate the effect of topiramate, and we did not have a long follow-up period after the treatment weeks, except in one study15 that had a 24-week follow-up without measuring outcomes. Additionally, the total sample size of the three studies used for pooling effect size of prolonged abstinence rate was 125 topiramate-treated smokers and 129 controls, which may be still underpowered to show significant difference, although the numeric difference favors topiramate. Time point prevalence was also reported as a measure for smoking abstinence rate. A recent placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial tested the efficacy and safety of varenicline in smokers with HIV27. Point prevalence abstinence at weeks 12 and 24 was used as a primary outcome. The pooled time point abstinence rate at week 12 was significantly higher in the topiramate group when compared with the control, which is the pooled effect of three studies and may be more representative than time point prevalence at earlier weeks. The major side effects of topiramate, as reported by the manufacturer, are paresthesia, fatigue, dizziness, decrease serum bicarbonate, hyperammonemia, abdominal pain, nephrolithiasis and disturbance in attention. The topiramate dose based on the available studies is 200 mg, started with a small dose and titrated slowly to the reported dose up to 12 weeks.

Limitations

There are some limitations in the current study. Firstly, it involves only clinical trial studies with only topiramate as an intervention for smoking cessation. Secondly, due to the insufficient number of the included studies, the publication bias and subgroup analysis cannot be performed. Thirdly, we were working on all possible outcomes regarding the effectiveness of topiramate on smoking cessation compared with the placebo and found the following outcomes:

Prolonged smoking abstinence rates were reported in three studies15-17 and all were included in meta-analysis.

Time point abstinence rates were reported in four studies13-15,17 and all were included in meta-analysis.

Cotinine level was reported in 2 studies: one dichotomized it into two categories: below and above 28 ng/mL, to discriminate between smokers and non-smokers14. The other study measured cotinine level at baseline only to show difference between males and females16. The combinability of the results is invalid.

Number of cigarettes was reported in 3 studies: in the first, the mean number of cigarettes smoked at the end of the treatment among topiramate group was 16.2 (±11.21 SD) while among the placebo it was 21.93 (±7.11 SD)28. The second represented means of cigarettes per week graphically without SD over the 12-week treatment with topiramate and during the 24-week follow-up period29. In the third, the average cigarettes across the topiramate group decreased from a mean of 19.2 cigarettes/day (±7.5 SD) to 6.7 cigarettes/day (±6.8 SD), with no data for placebo30. The combinability of the results is invalid.

CONCLUSIONS

The efficacy of topiramate in promoting smoking cessation, based on the available evidence, could not be established. We cannot recommend topiramate for smoking cessation in practice. A large clinical trial with sufficient power is required with longer follow-up times to demonstrate the efficacy of topiramate in smoking cessation.