INTRODUCTION

Smoking is a major public health issue, as it is a leading cause of preventable death and disease worldwide, contributing to more than 8 million deaths each year1. Despite the well-known health risks, many individuals struggle to quit smoking, and even those who manage to quit often have to go through several attempts before being able to successfully stop. As a result, there is a need for effective interventions to help smokers quit and reduce the burden of tobacco-related diseases, through the combination of therapeutic education, behavioral support, and pharmacotherapy for an effective cessation approach2. The 5As model and group behavioral therapy are evidence-based interventions for therapeutic education and behavioral support recommended in the guidelines, while nicotine replacement therapies, varenicline, and bupropion are the most effective medications2,3.

One popular approach for smoking cessation is Allen Carr's (AC) ‘easy way’ method4. This pharmacotherapy-free method is based on the idea that smoking is an addiction to the feeling of relief that cigarettes provide, rather than to the nicotine itself. According to this approach, by understanding and reframing the psychological dependence on smoking, individuals can overcome their addiction and quit smoking without experiencing withdrawal symptoms or weight gain.

The AC method has gained widespread popularity and has been implemented in several formats. One well-known format considers in-person group seminars, where trained facilitators guide participants through a structured program. These seminars, which typically last for 4 to 6 hours, are usually delivered to small groups of people, often around 20 participants or fewer. The interactive nature of these sessions fosters exploration of smoking habits, the questioning of beliefs, and insights into psychological motivations. After the initial seminar, participants often have the opportunity to attend two no-cost AC follow-up sessions5. Furthermore, the AC method offers online platforms including courses, webinars, and self-help materials5. Another tool is the book4 entitled ‘The Easy Way to Stop Smoking’, by Allen Carr and translated into several languages, which encapsulates the core principles of the approach. Over 15 million copies of this book have been sold globally.

Despite its popularity, the effectiveness of this unconventional approach remains a disputed topic in the literature due to the lack of a scientific basis. A recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) conducted by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), based on two studies, concluded that the AC method was as good as other pharmacotherapy-free smoking cessation methods, such as one-to-one support provided by local stop-smoking services6. The previous systematic review on the topic was conducted more than ten years ago by Rasch and Grainer7 and concluded that ‘The evidence is insufficient for the internationally widespread course Allen Carr’s Easy Way’.

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive and updated overview of the current state of the evidence on the effectiveness of the AC method for smoking cessation.

METHODS

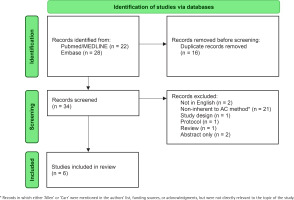

A systematic review of the literature was conducted on 29 March 2023 on PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. The search string used was: ‘Allen Carr (smoking OR tobacco)’. We did not apply any restriction on publication year, considering all scientific articles published before the search date. A total of 34 studies were retrieved through the search. In the first step, two reviewers (IP and MS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies for eligibility. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were discussed and resolved. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (SG) was designated to help making a final decision. In the second step, the full texts of the articles that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved and screened. The eligibility criteria for this review were as follows: 1) the study design was an RCT or an observational study; 2) the article was published in English; 3) the focus of the study was smoking cessation and, specifically, the use of the AC method; and 4) the outcome was a measure of the effectiveness of the AC method, either alone or compared with other smoking cessation techniques. No specific limits or exclusion criteria were imposed based on the primary outcome on smoking measures. Thus, all articles evaluating or investigating the AC method were included in the review, regardless of the specific smoking outcome they employed (e.g. smoking cessation, relapse, reduction).

For each publication satisfying the eligibility criteria, we collected: 1) general information on the publication (authors, year of publication, journal); 2) study characteristics (country, calendar period, study design, sample size); 3) type of smoking cessations technique(s) used (form of AC method and other smoking cessation tools); and 4) smoking cessation rate(s) after the period of observation. Main outcomes of eligible studies were synthesized for the review. Data extraction was performed using Microsoft Excel and EndNote X7.

Risk of bias assessment was performed for each included study to evaluate the methodological quality and potential sources of bias. The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS – I) tool8 was used to evaluate the risk of bias in one quasi-experimental design study and in one RCT that did not use randomization for participant assignment to the AC method or control group. The ROBINS-I tool classified bias risk as: low, moderate, serious and critical8. The Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) tool for randomized trials9 was employed to assess bias across multiple domains in two RCTs. This tool categorized studies as: low risk of bias, some concerns, and high risk of bias. Moreover, for two case-series studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool for case-series studies10 was applied. Case-series studies were categorized based on the percentage of ‘Yes’ answers in the JBI checklist as: low risk of bias (≤33%), moderate risk of bias (34–66%), or high risk of bias (≥67%)11. Two independent reviewers (IP and MS) conducted the risk of bias assessments for each study. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were discussed and resolved. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (AL) helped to make a final decision.

RESULTS

Out of 34 identified articles, six met the eligibility criteria and were included in the present systematic review (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the six included studies. Four were observational studies and two were RCTs. Five studies investigated the effectiveness of AC seminars, while one study focused on the use of the AC book.

Table 1

Study characteristics and cessation rates after attending Allen Carr (AC) method seminars or reading the AC book

| Author Year | Study design | Country (study period) | Sample size | Cessation tool | Cessation rates % (time) | OR (95% CI) | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seminar | |||||||

| Hutter et al.12 2006 | Observational | Austria (2002–2003) | 223a | AC single-session seminar | 40 (1 year) | - | Moderatef |

| Moshammer and Neuberger13 2007 | Observational | Austria (1999–2004) | 510b | AC single-session seminar | 51 (3 years) | - | Moderatef |

| Dijkstra et al.14 2014 | Observational | Netherlands (2011–2013) | 285 (124 vs 161) | AC single-session seminar vs no treatment | 41.1 vs 9.6 (13 months) | 6.52 (3.10–13.72) | Moderateg |

| Keogan et al.15 2019 | RCT | Ireland (2015–2017) | 300 (151 vs 149) | AC single-session seminar vs online Irish National service | 38 vs 20 (1 month) 27 vs 15 (3 months) 23 vs 15 (6 months) 22 vs 11 (1 year) | 2.36 (1.40–3.95)c 2.26 (1.22–4.21) 1.65 (0.92–2.96)c 2.17 (1.15–4.10)c | Some concernsh |

| Frings et al.16 2020 | RCT | UK (2017–2018) | 620 (310 vs 310) | AC single-session seminar vs Stop Smoking Service | 27.7 vs 33.5 (4 weeks) 21.6 vs 21.9 (12 weeks) 19.4 vs 14.8 (26 weeks) | 0.76 (0.54–1.07) 0.98 (0.67–1.44) 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | Some concernsh |

| Book | |||||||

| Foshee et al.17 2017 | Observational based on an RCTd | USA (2012–2013) | 52e (34 vs 18) | AC book vs no treatment | 29.4 vs 33.3 (6 to 12 months) | 0.83 (0.24–2.84)c | Seriousg,i |

d The study is randomized to either receive an AC book for free or be recommended to purchase it, while we considered the comparison between those who read the book and those who did not.

f Using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool for case-series studies10 (Supplementary file Table 1).

g Using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS – I) tool8 (Supplementary file Table 2).

i The study by Foshee et al.17 was categorized as a non-randomized study because it did not use randomization for participant assignment to the Allen Carr method (patients who read the book) or control group (patients who did not read the book).

Of the four observational studies included, two were case-series studies conducted in Austria and focused on the effectiveness of single-sessions of AC seminars at the workplace12,13. The study by Hutter et al.12 was conducted on a sample of 223 respondents (out of 308 participants) and found a one-year cessation rate of 40% among attendees of a single-session of the AC seminar. When assuming the same proportion of successful quitters among participants with unknown smoking status at follow-up, the cessation rate increased to 55%12. The observational study by Moshammer and Neuberger13 was based on a sample of 510 Austrian respondents (out of 515 participants) and found a three-year cessation rate of 51%. Self-reported results on smoking abstinence were partially confirmed by testing the urinary cotinine concentrations on a subsample of 10 people13.

The third observational study was conducted in the Netherlands and compared 13-month cessation rates in 124 smokers who attended a single-session AC seminar to those of 161 smokers in the general population14. The 13-month abstinence rate for participants who attended the AC seminar was 41.1% and that of participants in the control group was 9.6%. The corresponding multivariate adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was 6.52 (95% confidence interval, CI: 3.10–13.72), indicating a significantly higher likelihood of abstinence in the treatment group compared with the control group14. Self-reported abstinence was confirmed through cotinine analysis for subjects reporting abstinence.

The first AC RCT was conducted in Ireland by Keogan et al.15 who randomly assigned 300 study participants to either 5 hours AC single-session seminars (n=151) or to Health Service Executive National Smoking Cessation Service ‘Quit.ie’ (n=149)15. The AC seminar showed higher quit rates at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months compared with ‘Quit.ie’ (38, 27, 23, 22 vs 20, 15, 15, 11%, respectively, all p<0.05). The AOR of abstinence at three months for those who attended the AC seminar compared with those who used ‘Quit.ie’ was 2.26 (95% CI: 1.22–4.21)15. Self-reported quitting was validated using breath tests.

The most recent study on the AC method was conducted in the UK16. In this RCT, 620 individuals were randomly assigned to either a 4.5–6 hours AC single-session seminar (n=310) or the specialist Stop Smoking Service (SSS) treatment, which included nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (n=310). The authors found no significant difference in 26-week abstinence rates between the AC and SSS groups, 19.4% and 14.8%, respectively (risk difference=4.5%; 95% CI: -1.4–10.4; p=0.165)16. Smoking abstinence was verified using breath tests.

The study conducted by Foshee et al.17 in the USA was based on 92 patients with head and neck disorders who were randomized to either receive the AC book for free (n=48) or be recommended to purchase it (n=44). The results showed that those who received the book for free were more likely to read it than those who were only recommended to buy it (78% vs 52%; p=0.05). However, reading the book did not significantly impact smoking cessation, as 29.4% of the 34 participants who read the book quit smoking by the end of the study (6 to 12 months after receiving or buyng the book) compared with 33.3% of the 18 participants who reported not having read it (p=0.81)17.

The risk of bias assessments for the included studies are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–3. The two case-series studies and the quasi-observational study conducted by Dijkstra et al.14 were rated as having a moderate risk of bias. The RCT conducted by Foshee et al.17 was classified as having a serious risk of bias, whereas the other two RCTs raised some concerns within the domain of missing outcome data.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the results of this systematic review suggest that the AC seminar may be an effective intervention for smoking cessation. This is in line with the recommendations of the NICE, concluding that the AC seminar was as good as other pharmacotherapy-free smoking cessation tools6.

The included studies found high smoking cessation rates among individuals who attended AC seminars, with cessation rates ranging from 19% to 51%. It is worth mentioning that those quit rates are higher than those typically achieved using e-cigarettes as a cessation tool, which have been shown to have 6-month quit rates in RCTs ranging from 9% to 14%18.

An observational study found a significantly increased abstinence among those attending AC single-session seminars, compared with controls with no treatment14. Moreover, an RCT found that the AC seminar was significantly more effective than the ‘Quit.ie’ program in achieving abstinence, with higher quit rates at multiple time points after treatment and persisting to 12 months. Specifically, the 3-month quit rate was approximately doubled in people attending AC seminars, compared with those assigned to the online Irish National service15. However, the authors showed a higher mean weight gain after three months in the AC treatment group compared with the other group (3.8 vs 1.8 kg; p<0.01)10. Weight gain is a well-documented phenomenon in smoking cessation, often acting as a barrier against quitting or even a reason for relapse19,20. This result, divergent from the AC method’s premise of minimizing such weight gain5, underscores the complexity of smoking cessation interventions and their potential trade-offs. Exploring how quitting smoking, managing weight, and the features of the AC method are connected can help in better understanding its overall impact and in suggesting ways to improve quitting success.

When the AC seminar was compared with a specific treatment that included the use of NRT, no evidence of any clear difference between the two methods was observed16. Since the AC seminar does not require pharmacotherapy, it is a potentially attractive option for those who wish to quit smoking without the use of medications. Therefore, the lack of a clear difference in effectiveness between the AC seminar and treatment including NRT supports the efficacy of the AC seminar for smoking cessation.

In light of the AC book’s popularity as a best-seller, it is interesting to note that the literature on its effectiveness is extremely poor, with only one available study on the topic which did not yield significant evidence of its impact on smoking cessation rates12. Moreover, this study was not specifically designed to assess the efficacy of reading the AC book and it was rated as having a serious risk of bias.

The six studies included in the systematic review have some potential limitations. Firstly, the sample sizes were relatively small, with the largest study including only 620 participants. Therefore, while the AC seminar method appears to be promising, there is still limited evidence available to fully confirm its effectiveness. Further research with larger sample sizes is needed to strengthen the evidence base for the AC seminar method. Moreover, the studies used a variety of methods to verify smoking abstinence, including self-report, cotinine analysis, and breath tests. While self-report is the most commonly used method for assessing smoking status, it is subject to bias and may not accurately reflect actual smoking behavior. Therefore, the use of more objective measures, such as cotinine analysis and breath tests, is suggested to strengthen the findings of future studies. Additionally, all included studies raised some concerns in risk of bias assessment. This underscores the importance of conducting further high-quality research to enhance the overall quality of the evidence.

Strengths and limitations

There are several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this review. Notably, the scarcity of available RCTs investigating the AC method presents a limitation in terms of the robustness of the evidence. Although the observational studies included in this review suggest that the AC seminars may be effective for smoking cessation, these types of studies do not have the same strength as RCTs in terms of scientific evidence. To more definitively determine the effectiveness and the positioning of AC seminars in smoking cessation, RCTs comparing it to the available pharmacotherapeutic agents, including e-cigarettes, and non-pharmacotherapy interventions are needed. Moreover, the observed heterogeneity in the application of the intervention across studies introduces variability in the results, making direct comparisons challenging and potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the search was conducted only on two scientific databases (i.e. PubMed and EMBASE), potentially leading to the omission of relevant studies available in other databases. Additionally, excluding publications based on their language might be considered as a limitation of the present systematic review. However, none of the two non-English publications excluded would have been eligible because of other exclusion criteria. Another limitation of the present systematic review is the fact that the protocol was not prepared and it is not registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), which, although not mandatory, is recommended by guidelines on conducting systematic reviews.

Alongside these limitations, the inclusive analysis of different study designs, spanning both observational and RCTs, enriches the comprehensiveness of the evidence synthesized in this review and represents therefore a strength of this systematic review. Moreover, the rigorous screening process employed in study selection further enhances the reliability of the findings.

Implications

From a clinical perspective, the findings of this review hold relevant implications. While the AC method appears to be promising, the scarcity of high-quality RCTs hinders us from unequivocally endorsing it as a primary smoking cessation strategy. The observed variability in the application of the AC method emphasizes the importance of standardized implementation and underscores the need for additional research.