INTRODUCTION

An estimated 21% of 16-year-old students in Europe are current smokers and 13% report daily smoking1. Nicotine dependence develops quickly during adolescence and a large proportion of adolescents who smoke regularly will continue smoking during adulthood2-4. As with other health behaviours and addictions (e.g. alcohol, drug use, unsafe sexual practices, etc.)5, the early identification and treatment of adolescent tobacco use is important for preventing more serious short- or long-term health consequences6.

Adolescent tobacco users are recognized as a special population that requires tailored interventions for smoking cessation. Interventions targeting adolescent smokers have increased in number in recent years7,8. However, the lack of robust and adequately powered randomized controlled trials, coupled with complete reliance on models originally designed for adults, has limited and confounded the evidence regarding the efficacy of available interventions in supporting cessation among adolescents7-10. A 2017 Cochrane systematic review identified group-based behavioural interventions as the most promising approach, supporting the findings of an earlier meta-analysis of 48 trials involving adolescent smokers, which concluded that tobacco cessation programs are more likely to be effective if they are offered within the school setting10. Specifically, motivational enhancement intervention programs that are delivered in schools over an extended period, and which include multiple components, have been found to be the most effective approach for prevention of smoking initiation11, short-term smoking cessation and smoking reduction8.

The 2017 Tobacco Cessation Guidelines for High-risk Groups (TOBg Guidelines)12 were produced with the aim to develop and implement an innovative and cost-effective approach for the prevention of chronic diseases related to tobacco dependence by developing specialized tobacco cessation guidelines for high-risk populations. The TOBg Guidelines include a special chapter on tobacco treatment among adolescent tobacco users designed to assist both health and prevention practitioners in delivering evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions for adolescent smokers in various settings, with a special focus on interventions delivered in schools. The Guidelines are available online at http://TOB.g.eu/.

We conducted a pilot study to: 1) obtain feedback from prevention practitioners in terms of their satisfaction, knowledge and self-efficacy following exposure to the Tobacco Treatment Guidelines for Adolescents (TOBg Guidelines) and 2) examine the effectiveness of a school-based intervention, implementing the TOBg Guidelines on quit rates, among a sample of adolescent tobacco users.

METHODS

The pilot study consisted of two parallel studies.

Design of Study 1 — Testing TOBg Guidelines among prevention practitioners

In Study 1, we conducted a pre-post evaluation to examine the impact of the TOBg Guidelines and training program on prevention practitioners’ level of knowledge, expressed level of satisfaction with the guidelines, and reported the impact on their self-efficacy. Measurements took place before, immediately after, and at 6 months following exposure to the 1-day training program.

Participants of Study 1

Participants in the training program consisted of prevention practitioners employed in specialised Centres for the Prevention of Substance Use and the Promotion of Psychosocial Health in Greece (hereinafter ‘Prevention Centres’). In Greece, prevention practitioners have responsibility for the design and implementation of health-promoting/risk-averting interventions in schools and the community. The Prevention Centres are located in the major city of each prefecture of the country and are funded by the government. Their services cover several health-risk behaviours, including tobacco and other substance use, aggression and bullying. Prevention practitioners work directly with adolescents, both within and outside the school-setting, and they are thus presented with an opportunity to identify and intervene with adolescent smokers.

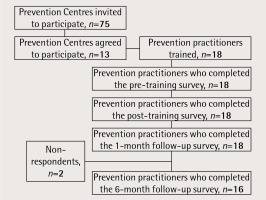

An invitation letter was sent to the administrators of all 75 Prevention Centres in operation in Greece in 2017. Thirteen Prevention Centres expressed their interest to participate in the study, delegating to the pilot study a total of 18 practitioners. Eligibility criteria set for the participation of practitioners in the study were: 1) be experienced in designing and implementing school-based interventions, 2) be experienced with working directly with adolescent students, 3) be available to participate in the TOBg Guidelines training session, and 4) have good knowledge of the English language (the TOBg Guidelines were available only in English). Current and past smoking status of the prevention practitioners were not among the eligibility criteria.

Procedure of Study 1

A 1-day training session was conducted in Athens, Greece, in March 2017. Participating practitioners received an electronic or hard copy of the TOBg Guidelines before the training. During the training, experts involved in the co-authorship of the guidelines presented and discussed evidence-based key recommendations pertaining to tobacco cessation among adolescent smokers. Training also included practical guidance for the implementation of a group-based smoking cessation intervention for school settings to assist students who smoke with quitting. Practitioners completed the TOBg provider survey, which measured their demographic and smoking characteristics, tobacco cessation knowledge and self-efficacy immediately before the training session (Time 1 – T1) and at the end of the training day (Time 2 – T2), in order to measure the immediate impact of the training session on their level of knowledge and their perception of self-efficacy. A follow-up survey (by e-mail) was conducted at 6 months following training (Time 3 – T3) to assess the prevention practitioners’ satisfaction, and their perception of self-efficacy, in developing smoking cessation interventions based on the TOBg Guidelines. Two email reminders were sent, at 7 and 14 days following the first contact, to those who had not responded. A phone call was made to anyone who had not responded to the reminders. All participants provided data at the post-training assessment at the 1 month follow-up, but only 89% provided data at the 6 months follow-up assessment (Figure 1).

Outcome measures and instruments of Study 1

Six areas of satisfaction were assessed: 1) assessment of practitioners’ overall satisfaction with the guidelines; 2) the appropriateness of guideline length, 3) ease of understanding, 4) extent to which new information was provided, 5) extent of missing information, and 6) perceived impact of the guidelines on the approach with which they address tobacco use with adolescents. Practitioners’ knowledge was assessed with the use of a 10-item questionnaire that was based on the information presented in the adolescents section of the TOBg Guidelines8. Practitioners’ perception of self-efficacy in delivering smoking cessation interventions was assessed using a 6-item questionnaire allowing responses on a 10-point rating scale; with 1 – indicating lack of confidence and 10 – extreme confidence. This has been adapted from previously published instruments13-16.

Design of Study 2 — Group-based smoking cessation intervention for adolescents

Study 2 examined the effectiveness of a pilot smoking cessation intervention that drew on the TOBg Guidelines and was delivered in a sample of high-schools in Greece. The primary outcome measure was adolescent smoking status assessed at baseline, at 1 month and at 6 months. Secondary outcome measures included reduction in student’s daily smoking consumption.

Participants of Study 2

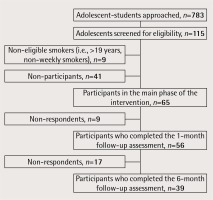

Student eligibility criteria for the study included: 1) weekly tobacco use, 2) interest in quitting smoking in the next 30 days, 3) being between the ages of 13 and 19 years, 4) willing to complete the study survey, and 5) have access to a telephone for follow-up. Eligible students were sought from within a convenience sample of 20 schools, the head-teachers of which responded positively to the invitation of the local practitioners. A total of 783 students participated in the initial information session, irrespective of their smoking status. Among them, 115 smokers accepted to be screened for eligibility. Following screening, nine students were deemed ineligible as they either were over the age of 19 years (n=6) or smoked less than weekly (n=3). Among eligible students (n=106), 41 students did not participate in the main phase of the intervention. Reasons for non-participation included: expressed concerns that their parents and/or teachers would find out that they smoke (especially given the required parental consent), hesitations to make the time commitment for the whole duration of the intervention and the ‘not convenient’ timing of the intervention (close to final school exams). Finally, 65 eligible students agreed to participate in the main phase of the intervention. The recruitment flow diagram is presented in Figure 2.

Procedure of Study 2 – Intervention

Prevention practitioners, who were trained in the TOBg Guidelines (Study 1), approached one high-school under their area of responsibility and delivered a 2-hour information session addressed to all students, smokers and non-smokers (baseline). The session provided information about the benefits of abstaining from smoking. At the end of the session, adolescents were invited to fill-in an anonymized survey assessing demographic characteristics and smoking related history. Practitioners screened student surveys and invited eligible adolescent smokers to join a group-based cessation program offered at their school in the weeks immediately following the baseline session. Drawing on the evidence-based recommendations included in the TOBg Guidelines8, the program comprised three 2-hour group sessions based on motivational enhancement and cognitive-behavioural techniques, as well as the provision of self-help material. A paper-based follow-up survey assessing their smoking status was conducted at 1 month (± 2 weeks) and a telephone-based survey at 6 months (± 2 weeks) following baseline.

Outcome measures and instruments

The primary outcome measure was the self-reported point prevalence of smoking abstinence assessed at 1 month and at 6 months follow-up, according to the Russell Standard17. A secondary outcome measure was the proportion of students reporting a reduction by at least 50% in cigarettes smoked per day (CPD). The study also considered the proportion of students reporting a reduction of 2 or more CPD at follow-up. For any adolescents with missing data we assumed that they had returned to active smoking, according to the Russell Standard17.

Ethics procedures

Prevention practitioners provided individual written informed consent. Eligible students and their parents/guardians provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Athens University Mental Health Research Institute (UMHRI).

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to summarize the demographic characteristics of Study 1 and Study 2 participants. Pearson’s chi-squared statistics were used to examine categorical data and paired samples t-tests for continuous data. The significance level was set at a = 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to analyse all data.

RESULTS

Results of Study 1 — Testing TOBg Guidelines among prevention practitioners

Participant characteristics

Demographic and educational characteristics of the prevention practitioners are presented in Table 1. The majority were female (88.9%), psychologists, with mean age of 41.4 ± 6.1 years standard deviation (SD). Based on self-reports, 11.8% of the practitioners were current smokers, 41.2% were past smokers and 47.0% had never smoked.

Satisfaction, knowledge, and self-efficacy

Table 2 presents the results of prevention practitioners’ satisfaction with the Guidelines. The majority of the practitioners (76.9%) reported that they were ‘extremely satisfied’ with the TOBg Guidelines for adolescents and that they considered them easy to understand. However, almost 1 in 4 (23.1%) reported that the guidelines were missing information and 15.4% that they were too long. The majority of practitioners indicated that the guidelines will influence the manner in which they intervene with adolescents who smoke. While the majority of practitioners agreed (‘very much’) that the guidelines offered new information, 30.8% of the total sample reported that this was only ‘somewhat’ true.

Table 2

Level of satisfaction and perceived utility of the TOBg Guidelines among prevention practitioners at the 6 month follow-up assessment (n = 13)

Table 3 presents a summary of the percentage of prevention practitioners who responded correctly to the knowledge questions. While there were positive changes observed in some of the knowledge assessment questions, no statistically significant changes were observed. In two cases, there was a decrease in correct responses following the training.

Table 3

Difference in the percentage (%) of correct responses of prevention professionals regarding tobacco treatment knowledge before and after the TOBg training program (correct answers in italics)

There was a significant increase in the perceived self-efficacy of practitioners regarding the delivery of evidence-based treatments for tobacco use following the training in all six areas assessed at the 1 month and 6 months follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4

Prevention practitioners’ perceived self-efficacy related to the delivery of evidence-based smoking cessation interventions before and after the TOBg training program

| Mean scorea | pb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training T1 | Post-training T2 | At 6 months follow-up T3 | T1 vs T2 | T1 vs T3 | |

| Variable | n=18 | n=18 | n=13 | n=18 | n=13 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||

| How confident are you in….. | |||||

| …advising adolescents to quit smoking | 7.22 | 8.28 | 8.77 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| …providing brief smoking cessation counseling (<5 minutes) | 6.61 | 7.83 | 8.62 | 0.106 | 0.016 |

| …providing counseling to adolescent smokers not motivated to quit | 6.78 | 7.72 | 8.23 | 0.056 | 0.025 |

| … assisting with setting a date to quit smoking | 6.06 | 7.61 | 8.00 | 0.027 | 0.032 |

| …providing some other form of smoking cessation counselling intervention | 6.94 | 8.44 | 8.38 | 0.007 | 0.028 |

| … arranging follow-up in person or by phone with adolescent smokers thinking about quitting smoking | 6.89 | 8.28 | 8.46 | 0.054 | 0.027 |

Results of Study 2 — Group-based cessation intervention for adolescents

Participant characteristics

Table 5 summarizes the demographic characteristics of student participants. Participants (41.9% females) had a mean age of 17.1 (SD: ± 0.84) years. At baseline, 80.0% of tobacco users reported smoking daily and 9.2% reported smoking at least once a week. Almost half of the participants (47.7%) reported smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day.

Table 5

Characteristics of adolescent smoker participants (n=65)

Quit/smoking reduction rates

No significant increase in smoking abstinence was documented at the 1 month and 6 months follow-up (Table 6). Sixty-three per cent of participants reported a 50% or greater reduction in cigarettes smoked per day at the 1 month follow-up (Table 6). This decreased to 23.1% of the participants at the 6 months follow-up. Similar trends were noted for a reduction of 2 or more CPD. Much of the observed decrease in smoking reduction at the 6 months follow-up was due to losses between the follow-up at 1 month and at 6 months.

Table 6

Proportion of adolescents self-reporting abstinence or smoking reduction at the 1 month and at the 6 months follow-up assessment

| At 1 month follow-up assessment | At 6 months follow-up assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Abstinent/participants reached | 0/56 | 0 | 1/39 | 2.6 |

| Abstinent/participants reached with missing data replaceda | 0/65 | 0 | 1/65 | 1.5 |

| Reduction of ≥50% in CPD/participants reached | 30/48 | 62.5 | 9/39 | 23.1 |

| Reduction of ≥50% in CPD/participants reached with missing data replaceda | 30/65 | 46.2 | 9/65 | 13.8 |

| Reduction in CPDb/participants reached | 38/48 | 79.2 | 19/39 | 48.7 |

| Reduction in CPD/participants reached with missing data replaceda | 38/65 | 58.5 | 19/65 | 29.2 |

DISCUSSION

This pilot study examined the real-world performance of the 2017 TOBg Guidelines8 addressing tobacco cessation for adolescents. The TOBg Guidelines identified school-based interventions as being among the most promising approaches for influencing tobacco use among adolescents and, therefore, the present study focussed on the school setting. Specifically, the study: 1) exposed a group of prevention practitioners who work with schools in Greece to the TOBg Guideline recommendations for adolescent smoking cessation, 2) trained them on a school-based intervention that drew on the recommendations, and 3) tested its influence on the smoking behavior of the participants.

Practitioners exposed to the TOBg Guidelines reported high rates of satisfaction with their use and most of them considered that the guidelines will inform the preparation of future interventions targeting tobacco use prevention and cessation among adolescents. There were some mixed reactions among practitioners in terms of the degree to which the guidelines provided new information. Furthermore, our study did not document any significant changes in the level of practitioners’ knowledge following their exposure to the guidelines. The latter may be due to the already high rates of knowledge among the practitioners who participated in the study, given that they were all experienced prevention professionals working in Prevention Centres. Our pilot study found that practitioners’ self-efficacy in delivering tobacco treatment to adolescents who smoke increased significantly following exposure to the TOBg Guidelines and training. Given that self-efficacy has been found elsewhere to be highly correlated to rates of tobacco treatment delivery among health care providers12,13, this finding could be considered as an important outcome of our pilot intervention and an important target for increasing intervention rates18,19.

The 3-session group-based intervention tested in schools was associated with a reduction in cigarettes smoked per day among adolescent participants, although no significant effect on smoking abstinence was observed. These findings are consistent with those reported in other studies, which have shown that school-based interventions, if well designed, can be effective in reducing short-term abstinence and reducing daily cigarette consumption; however the effectiveness on long-term smoking abstinence remains unclear7,8,15. While the primary study outcome was complete abstinence from smoking, it should be noted that reducing tobacco consumption may increase the chance of quitting in the future. The school-based intervention was counselling-based and nicotine replacement treatments were not provided to students. Our student sample reported fairly high rates of nicotine dependence and as such it is possible that the addition of nicotine replacement therapy may have increased cessation rates.

Besides elements pertaining to the study design, it would be important to note that the effectiveness of tobacco cessation interventions that target adolescents may depend on numerous factors, ranging from intra-personal characteristics (e.g. level of nicotine dependence, skills, knowledge, attitudes, etc.), to inter-personal (e.g. parental and peer influences), community (e.g. availability of tobacco selling points or of screening and smoking cessation services), and public policy influences (e.g. prices of tobacco products, law enforcement, etc.)8,19,20. The present study did not take into account the smoking culture (e.g. prevalence, rules, teachers who smoked, etc.) in the schools where the interventions took place, which may have impacted on the outcome of the intervention as a whole. Also, our study took place in Greece where the prevalence of tobacco use in the general population is among the highest in Europe21, with selling prices of cigarettes lower than in many other EU countries22, and where policies such as smoke-free areas or restrictions of cigarette sales to minors are poorly enforced23,24.

Both the content and length of intervention appear to be important predictors of successful smoking cessation outcomes in adolescent samples, with higher cessation rates found for programs involving motivational enhancement and lasting for at least five sessions10,25. Consistent with the data, practitioners involved in the present study reported concerns that while the intervention was feasible, the period allowed for the delivery of the school-based cessation intervention was not sufficient, as the intervention was delivered towards the end of the school year when the high-school students begin to focus on their final exams. In all schools, practitioners were able to complete only 3 group-based sessions with the adolescents, prior to the summer holidays, and this was in their opinion a factor that hindered the impact of the intervention. Moreover, the proximity of the implementation period to the final school exams and summer vacations was potentially an additional limiting factor in achieving higher recruitment and cessation rates. Future interventions should be planned to start early in the school year, so that the necessary optimum duration for the intervention can be ensured.

Limitations

The study findings should be interpreted in the light of several additional limitations. These include the relatively small sample size and the use of a non-randomized design. The small sample size of the prevention practitioners may have masked improvements in the knowledge base of the participants following exposure to the Guidelines. The lack of a control group means that we are unable to confirm any causal relationship between the intervention and changes in smoking outcomes, and it is possible that some participants would have quit smoking without the support of the current intervention. Two of the 18 prevention practitioners involved in the study were current smokers at the time of the intervention, thus their personal smoking status may have had a negative impact on the effectiveness of their intervention in schools. Given that these were a minority of practitioners, and that they were delivering a standardized curriculum, the overall effect on our study findings is expected not to be large. Furthermore, a significant number of students, who initially expressed interest in participating in the group-based cessation program, declined the opportunity to enrol, citing concerns about parental consent. While only 15% of data were missing among adolescents sampled at the 1 month follow-up, this increased to 40% at the 6 months follow-up. The follow up at 6 months occurred during the summer vacations (August–September), which may have been an additional obstacle to reaching students. Future programs should be designed to minimize this barrier to participation.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite limitations, the present study showed that the TOBg Guidelines were received with satisfaction among prevention practitioners working with adolescents and increased practitioners’ self-efficacy for delivering evidence-based programs targeting adolescent tobacco users. Although our study did not document an effect on smoking abstinence among the majority of adolescents, it adds to the existing evidence regarding the effects of school-based smoking cessation interventions that draw on cognitive behavioural and motivational enhancement strategies, and the potential of such interventions to reduce daily tobacco consumption in a real-world setting. Further studies, with larger samples, are needed to confirm the effects observed in this pilot study based on the TOBg Guidelines.