INTRODUCTION

About 600,000 non-smokers in Greece are exposed to secondhand smoke (SHS) with an estimated 19,000 Greek people dying from tobacco-related diseases annually1. SHS is a risk factor for respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), decreased lung function2, 3 and cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as coronary heart disease (CHD)4–7. It is estimated that 28% of global deaths attributable to SHS are children8, highlighting the need to target vulnerable populations from the world’s most preventable cause of death9.

Article 8 of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC)10 outlines the total elimination of smoking indoors in order to reduce SHS exposure. When properly enforced, national indoor smoking ban legislation reduces SHS exposure by as much as 90%11, immediately improving respiratory and sensory symptoms and reducing myocardial infarctions (MI) by 20-40% within months following ban implementation11. It also provides smokers with a supportive environment to quit12, 13, encourages smoke-free homes and results in either a neutral or positive economic impact on businesses including restaurants and bars11, 14.

Since ratification of the WHO FCTC in Greece, smoking prevalence has been declining from 41% in 200615 to 38% in 2009 and 32.6% in 201416. Despite a decline in prevalence of smoking and implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free law in 201017, SHS exposure is a major concern in Greece, where compliance with smoking bans is poor17, leaving 9 in 10 Greeks exposed to SHS when frequenting bars or nightclubs1, 18. Furthermore, as youth are often either employed at or frequent bars19 they report more SHS exposure at bars in Greece12, it is clear that they are put at high risk through chronic SHS exposure.

Previous studies in Ireland showed successful compliance with smoke-free bans in bars with over 80% of the population supporting the bans20. Self-compliance also has been found to be positively associated with support in Malaysia, Thailand21, Canada, United States, United Kingdom and Australia22. Support for smoking bans identifies the need for behavioral changes at societal23 and individual levels24.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to summarize the characteristics of supporters of the smoking ban in bars by smoking status in Greece and to identify factors related to supporting the ban in bars using the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) data, so as to help design tools that will improve support and compliance of the smoking ban and consequently improve smoking prevention and cessation throughout Greece and internationally.

METHODS

GATS methodology

A cross-sectional study design was applied using data from the GATS collected from a nationally representative sample of Greek residents >15 years of age in 2013. The GATS is considered a global standard for monitoring tobacco control25 using a standardized protocol for the administered questionnaire, sample design, data collection and management procedures. The GATS gathers information on respondents’ demographics, tobacco use and cessation, SHS, economics, media and knowledge as well as attitudes and perceptions towards tobacco use26.

Greece is home to approximately 10,800,286 people from a 2011 census27. The GATS used the 2002 and 2011 census data to apply a multistage geographically clustered sample design for nationally representative results. It was completed in four stages starting with the four major regions of Greece, then primary sampling units (PSU), followed by randomly selecting households and then residents18. The response rate of the 2013 GATS was 69.6% with a coverage rate of 93.3%18. A total of 6600 households totaling 4359 respondents were included in the GATS18.

Secondary analysis methods

A complex survey data analysis was performed using a weighted survey set for all analyses in the current study (PSU, strata and weights used as provided by the GATS) producing percent estimates and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI). The current study population, a total of 3961 people, consisted of 1588 current smokers and 2373 non-smokers who answered “yes” or “no” to the question, “Do you support the law that prohibits smoking inside bars?” and was used as the outcome variable in the analysis. The 9.13% of the total population who answered “Don’t know” or “Refused” were not included in the analysis. The socio-ecological model (SEM) framework28 was used to identify factors related to support for the smoking ban in bars at the individual level.

Independent variables included age, gender, education, marital status, occupation, knowledge, and beliefs. In addition, smoker-specific factors, “intention to quit” and “dependency on tobacco” were included for smokers. All “Refused” answers were not included in the analysis and accounted for <5% of the observations.

Raw data from the GATS for age (with imputation) was transformed from a continuous into a categorical variable to represent those of the original 2013 Greek GATS report. Level of education included only adults over the age of 25 years. Respondents aged 15-24 (a total of 382 respondents) were not included because they were too young to belong to certain educational categories. Separated or divorced were combined for marital status. “Unemployed, able to work” and “Unemployed, unable to work” were combined into one category for the variable occupation. For smoking status, a smoker was identified as a person who answered smoking “Daily” or “Less than daily”. The variable “knowledge” was created as a single, new continuous variable that combined all 11 GATS knowledge questions with “yes” answers. Respondents were asked, “Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cause the following… Serious illness? Stroke? Heart attack? Lung cancer? Bladder cancer? Stomach cancer? Brain cancer? Premature birth? Bone loss? Are cigarettes addictive? And can smokeless tobacco cause serious illness?”. Scores ranged from 0-11. Intention to quit included responses, “quit within the next month, thinking to quit within the next 12 months, quit someday but not within the next year, not interested in quitting” and “Don’t know”. Dependency on tobacco was measured by time of first cigarette after waking, while 57 observations were missing accounting for 3.4% of smokers.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the outcome variable by exploratory variables were summarized for smokers and non-smokers. Univariate logistic regression analyses were used in order to find which factors were related to support for the smoking ban in bars. Following this, logistic regression analysis in a stepwise method (p for entry <0.05, p for removal <0.10) was used in order to identify independently related factors with support for the bans in bars among smoker and non-smoker subpopulations. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed from the results of the logistic regression analyses. All reported p-values were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software (version 13.0).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Prevalence of smoking in Greece in 2013 was 38.2% (95% CI: 36.2-40.2), with 51.2% (95% CI: 47.9-54.4) of men and 25.7% (95% CI: 47.9-54.4) of women being current smokers. Smoking prevalence differed between youth and older adults with 30.0% (95% CI: 24.1-36.7) of the 15-24 year olds and 39.9% (95% CI: 37.9-41.9) over the age of 25 being smokers.

The smoking ban in bars in Greece was supported by 50.5% (95% CI: 46.5-54.4) of the total population. In total, 74.9% (95% CI=70.1-79.1) of non-smokers and 13.7% (95% CI=10.6-17.5) of smokers supported the smoking ban in bars.

As seen in Table 1, in the overall population, a higher percentage of those aged 65 and over supported the ban in bars compared to only 48.6% of youth (ages 15-24). Non-smokers showed that older adults (>65 years old), females, those with lower education, widowed, retired and those who believed SHS causes lung cancer had higher percentages of support than their respective modalities (Table 1). Smokers who supported the ban in bars had similar patterns as non-smokers but showed an overall lower support for the ban based on all factors examined.

Table 1

Percentage (with 95% Confidence Intervals) of overall population, smokers and non-smokers >15 years old who supported the ban in bars by individual characteristics (GATS, 2013)

| Overall Support | Smoker Support | Non Smoker Support | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage (95% CI) | Percentage (95% CI) | Percentage (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 15-24 | 48.6 (40.4-56.9) | 10.2 (5.0-19.9) | 65.3 (55.8-73.7) |

| 25-44 | 41.8 (37.2-46.5) | 11.5 (8.5-15.3) | 74.0 (68.0-79.1) |

| 45-64 | 48.3 (42.4-54.3) | 16.4 (12.6-21.1) | 74.3 (67.2-80.2) |

| 65+ | 74.0 (68.6-78.7) | 22.6 (15.8-31.4) | 84.4 (79.0-88.6) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 60.5 (56.0-64.8) | 15.9 (12.4-20.2) | 77.0 (72.6-81.5) |

| Male | 40.7 (36.2-45.3) | 12.5 (10.0-15.4) | 71.3 (64.6-77.1) |

| Education1 | |||

| Primary or less | 70.0 (62.8-76.9) | 21.4 (14.3-30.7) | 81.1 (73.8-86.8) |

| Secondary | 51.3 (45.4-57.0) | 18.1 (12.6-25.2) | 76.6 (68.0-83.4) |

| High School | 45.2 (39.8-49.6) | 12.0 (9.1-15.6) | 76.3 (70.0-81.7) |

| College | 45.0 (38.6-50.7) | 12.9 (9.4-17.4) | 74.2 (67.0-80.3) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 41.7 (36.2-47.4) | 9.7 (6.7-13.9) | 66.7 (58.7-73.8) |

| Married | 53.4 (48.9-57.8) | 15.7 (12.9-18.9) | 77.0 (71.9-81.4) |

| Divorced 2 | 30.7 (21.6-41.6) | 13.5 (7.7-22.7) | 73.4 (57.7-85.1) |

| Widowed | 77.4 (69.5-83.8) | 23.8 (13.0-39.5) | 87.6 (80.5-92.4) |

| Occupation | |||

| Government | 45.4 (36.1-54.9) | 16.1 (10.6-23.8) | 76.3 (65.4-84.6) |

| Non-Government | 42.1 (35.8-48.6) | 11.7 (8.6-15.8) | 72.0 (63.9-78.9) |

| Self-Employed | 34.4 (27.2-42.4) | 11.8 (7.7-17.7) | 65.9 (56.3-74.4) |

| Student | 56.4 (48.6-63.9) | 14.2 (6.0-29.9) | 69.1 (60.1-76.9) |

| Homemaker | 64.1 (58.2-69.6) | 19.7 (12.4-29.9) | 78.4 (71.8-83.9) |

| Retired | 68.2 (62.1-73.7) | 19.7 (14.0-27.0) | 83.4 (77.3-88.1) |

| Unemployed3 | 40.9 (33.5-48.8) | 10.3 (6.2-16.6) | 71.9 (61.0-80.7) |

| SHS causes lung cancer in adults | |||

| No | 20.5 (14.9-27.5) | 3.9 (1.6-9.1) | 41.4 (27.0-57.5) |

| Yes | 56.9 (52.7-61.2) | 18.0 (15.2-21.2) | 77.3 (72.8-81.3) |

| Don’t know | 36.1 (33.2-52.8) | 5.8 (3.4-9.8) | 69.7 (58.2-79.1) |

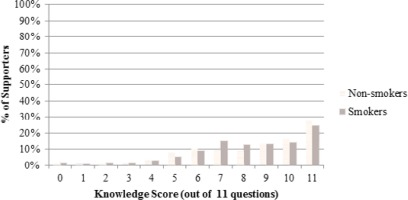

For knowledge of diseases caused by smoking, the majority, 95% (95% CI= 92.4-96.7) of the smoker population knew smoking could cause lung cancer whereas only 27.8% (95% CI= 22.6-33.6) knew it could also cause bone loss. Among non-smokers, 97.1% (95% CI=95.2-98.2) knew it could cause lung cancer compared to 40.4% (95% CI=34.6-46.5) who knew it could cause bone loss. Figure 1 shows individuals who supported the ban by smoking status and the amount of knowledge they had on smoking-related diseases out of an 11-point score.

Figure 1

Smokers and Non-smokers >15 years old who supported the smoking ban in bars (%) by the number of questions answered correctly (total of 11 questions) on smoking health effects

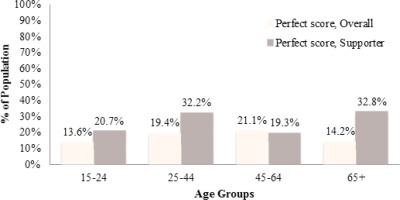

Those who supported the ban in bars had higher proportions of a perfect knowledge score compared to the general population, except for those aged 45-64 who had almost equivalent scores. Proportion of perfect knowledge score among supporters of the ban was 24% among smokers and 27.4% among non-smokers. In the overall population, those 15-24 years old had the lowest perfect score knowledge than all other age groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Proportion of those who had a perfect score (11/11 questions) for knowledge of smoking-related harms among the overall population and those who supported the ban in bars (Supporter) by age group

Supporting the ban in bars by intention to quit showed that 26.0% (95% CI: 8.6-56.7) of those who planned to quit within the month, 20.8% (95% CI: 14.3-29.2) within the next 12 months, 12.3% (95% CI: 9.3-16.0) someday but not in the next year, 13.4% (95% CI: 10.1-17.5) who were not interested to quit at all and 10.2% (95% CI: 5.9-17.4) who “didn’t know”, supported the ban in bars. For support by dependency, 10.2% (95% CI: 6.4-15.6) who had their first cigarette within <5 minutes, 13.3% (95% CI: 10.5-16.7) within 6-30 minutes, 14.2% (95% CI: 10.0-19.8) within 31-60 minutes and 19.6% (95% CI: 2.6-29.1) > 60 minutes of waking up supported the ban in bars.

Univariate analysis

Univariate analysis between support for the ban and smoking status in the overall population was highly significant (p<0.001). Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the univariate analysis for smokers and non-smokers. For smokers, supporting the ban in bars was significantly related (p<0.05) to being over age 65, having high school or college education, and being married. Among non-smokers, support for the smoking ban in bars was significantly related to being ages 45-54 or >65, male, married or widowed (Table 2).

Table 2

Results of Univariate analysis for demographic characteristics related to support for ban in bars among smokers and non-smokers >15 years of age (GATS, 2013)

| Smokers | Non-smokers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | P-value | OR | (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 15-24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 25-44 | 1.14 | (0.50-2.59) | 0.760 | 1.51 | (0.98-2.34) | 0.065 | |

| 45-64 | 1.72 | (0.75-3.98) | 0.201 | 1.54 | (1.06-2.23) | 0.025 | |

| 65+ | 2.57 | (1.05-6.31) | 0.039 | 2.88 | (1.72-4.79) | 0.000 | |

| Gender | Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 0.75 | (0.52-1.10) | 0.142 | 0.72 | (0.55-0.96) | 0.024 | |

| Education1 | Primary< | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.81 | (0.43-1.55) | 0.525 | 0.76 | (0.51- 1.15) | 0.188 | |

| High School | 0.50 | (0.28-0.89) | 0.019 | 0.75 | (0.48-1.18) | 0.207 | |

| College | 0.54 | (0.30-1.00) | 0.048 | 0.67 | (0.40-1.11) | 0.119 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Married | 1.73 | (1.08-2.77) | 0.022 | 1.67 | (1.21-2.31) | 0.002 | |

| Divorced2 | 1.46 | (0.67-3.09) | 0.327 | 1.38 | (0.64-2.96) | 0.402 | |

| Widowed | 2.91 | (1.25-6.77) | 0.013 | 3.54 | (1.93-6.48) | 0.000 | |

| Occupation | Government | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Non-Government | 0.69 | (0.38-1.23) | 0.228 | 0.80 | (0.45-1.44) | 0.450 | |

| Self-Employed | 0.70 | (0.35-1.38) | 0.300 | 0.60 | (0.32-1.14) | 0.116 | |

| Student | 0.86 | (0.30-2.50) | 0.782 | 0.70 | (0.42-1.17) | 0.166 | |

| Homemaker | 1.28 | (0.61-2.67) | 0.512 | 1.13 | (0.60-2.13) | 0.698 | |

| Retired | 1.28 | (0.68-2.42) | 0.443 | 1.56 | (0.88-2.77) | 0.123 | |

| Unemployed 3 | 0.60 | (0.29-1.25) | 0.172 | 0.80 | (0.41-1.53) | 0.487 | |

Table 3

Results of Univariate Analysis for individual factors and smoker-specific factors related to support for ban in bars among smokers and non-smokers (GATS, 2013)

| Smoker Support | Non-smoker Support | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | P-value | OR | (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| SHS causes lung cancer in adults | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 5.37 | (2.15-13.44) | <0.001 | 4.82 | (2.62-8.84) | <0.001 | |

| Don’t know | 1.52 | (0.53-4.37) | 0.437 | 3.25 | (1.64-6.42) | 0.001 | |

| Knowledge1, continuous | |||||||

| Did not know | 1.00 | ||||||

| Did know | 1.28 | (1.19-1.39) | <0.001 | 1.14 | (1.07-1.23) | <0.001 | |

| Smoker-specific factors | |||||||

| Intention to quit… | |||||||

| Within month | 1.00 | - | - | - | |||

| Within 12 months | 0.75 | (0.19-3.01) | 0.683 | - | - | - | |

| Someday2 | 0.40 | (0.10-1.54) | 0.182 | - | - | - | |

| Not interested | 0.44 | (0.11-1.70) | 0.234 | - | - | - | |

| Don’t know | 0.33 | (0.08-1.39) | 0.130 | - | - | - | |

| Time of first cigarette after waking | |||||||

| <5 minutes | 1.00 | - | - | - | |||

| 6-30 minutes | 1.35 | (0.77-2.38) | 0.295 | - | - | - | |

| 31-60 minutes | 1.47 | (0.78-2.78) | 0.239 | - | - | - | |

| More than 60 minutes | 2.16 | (1.05-4.44) | 0.037 | - | - | - | |

For both smokers and non-smokers, having the belief that SHS can cause lung cancer and increased knowledge of the harm of smoking were significantly related (p<0.05) to increased support of the ban in bars. In regards to dependency, time of first cigarette being over 60 minutes, was positively related to an increase in support (p<0.05) compared to those who answered that they had their first cigarette within 5 minutes of waking up (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

Following a backwards stepwise multiple regression for smokers and non-smokers, being 65 and over compared to 15-24 was significantly (p<0.05) related to supporting the ban in bars. In addition, “belief SHS can cause lung cancer” and increased “knowledge of smoking-related health effects” were factors significantly related to increased support of the ban in bars among smokers and non-smokers. Female gender was an additional factor that was significantly related (p<0.05) to increased support of the ban in bars compared to males among non-smokers (Table 4).

Table 4

Results of Multivariate Stepwise Regression Analysis for supporting the smoking ban in bars among smokers and non-smokers in Greece (GATS, 2013)

| Smokers | Non-smokers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | P-value | OR | (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age | |||||||

| 15-24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 25-44 | 1.01 | (0.48-2.17) | 0.964 | 1.30 | (0.85-2.01) | 0.228 | |

| 45-64 | 1.54 | (0.71-3.37) | 0.268 | 1.27 | (0.86-1.86) | 0.220 | |

| 65+ | 2.69 | (1.07-6.75) | 0.035 | 2.58 | (1.51-4.40) | 0.001 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | - | - | - | 1.00 | |||

| Male | - | - | - | 0.72 | (0.53-0.97) | 0.031 | |

| SHS causes lung cancer in adults | |||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 3.80 | (1.47-9.88) | 0.006 | 4.17 | (2.23-7.79) | <0.001 | |

| Don’t know | 1.60 | (0.56-4.64) | 0.376 | 4.24 | (2.12-8.49) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge | - | ||||||

| Did not know (0/10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Did know1, continuous | 1.22 | (1.13-1.32) | <0.001 | 1.13 | (1.06-1.22) | 0.001 | |

DISCUSSION

Given the low compliance of the smoking ban in bars in Greece17, this was the first study to examine the individual factors related to supporting the ban in bars using the 2013 GATS data. In general, Greece has a lower average support for the smoking ban in bars of 50.5% compared to the European average of 65%20.

Unsurprisingly, this study found that over 85% of smokers did not support the smoking bans in bars versus 25% of non-smokers. Proper implementation of smoke-free legislation enforces behavioral changes that consequently lead to changes in attitudes, beliefs13 and increased support14. In Greece, where the smoking ban legislation is not properly enforced, alternative approaches are needed to improve support. To bypass the issues around poor compliance in Greece, a focus should be given to actively changing behavior, through knowledge and beliefs among smokers, especially the youth, to improve support of the smoking ban and ultimately improve self-compliance of the ban20–22.

The percentage of smokers, who supported the ban in bars, did not differ significantly by gender. Among non-smokers, female gender showed a significant positive relation to support compared to men. This finding is in line with a previous study, regarding factors related to having an in-home smoking ban in Europe, that found women were more likely to be supportive than men29.

Also, in line with previous studies from other countries13, 22, 30, 31, this study showed that supporting the ban was more likely with older age (>65 years of age), believing SHS causes lung cancer, and having increased knowledge on harm caused by smoking. Although previous studies had differing national policies, populations, and varying contextual situations, results of this study show that factors related to support of the smoking bans are similar in the Greek context as well. Furthermore, the current study finding that older individuals are more likely to support the ban in bars is in line with factors related to in-home smoking bans in Europe29. According to the results of the current study, in the overall population, a perfect score for knowledge on smoking-related harm was low, and even more so among the youth, further highlighting the gap in knowledge among the Greek population. Communication strategies should aim to advance health literacy and public awareness on active and passive smoking-related harm. Increased public awareness may also prompt non-smokers to advocate for enforcement of the law. Building on beliefs that SHS causes harm leads to compliance with smoke-free legislation even when norms surrounding social acceptability of smoking are not addressed20,30.

The multivariate analysis showed that smoking specific indicators, dependency and intention to quit, were not significantly related to supporting the ban in bars. Although not identical in terms of factors examined, previous studies reported that dependency among college students in Greece was a predictor for non-compliance of smoking bans32 and lower cigarette consumption was also related to an increase in support for the smoking ban in bars22.

A previous study found that adult smokers in Europe quit smoking for two major reasons, becoming ill or gaining knowledge on smoking-related harm. Interestingly, the latter was the major reason reported for cessation among adults in Greece33. Based on current findings, half of Greek youth (15-24 years old) are supportive of the ban in bars, regardless of smoking status. With this in mind and the fact that youth are often employed and frequent bars19, rather than wait for morbidity to induce change, public health professionals can be proactive through taking a preventive approach. Since knowledge is strongly related to supporting the ban in bars and quitting smoking, it appears that health literacy is a key factor that must be strongly considered for interventions aimed at tobacco prevention and cessation. This is of utmost importance among the youth, where successful prevention will lead to creating a future smoke-free generation. Moreover, the fact that in the current study population only 30% of youth ages 15-24 were smokers compared to almost 40% of those 25 years old and over, signifies that conditions exist to achieve this aim.

The current study strengths included a representative sample size, sound methodology and high response and coverage rates18. The current analysis is limited to individual factors where there may be other factors related to supporting the ban in bars. In addition, as with all cross-sectional studies, none of the results assumes causality. Further research is needed to support recommendations in order to make evidence-driven policy decisions to maximize effectiveness of WHO FCTC outcomes. Qualitative analysis may contribute to explain how older age, regardless of lower education and smoking status, is associated with support of the ban in bars.

CONCLUSIONS

Interventions are needed to advance health literacy and awareness with regard to smoking and passive smoking-related harm. This will improve compliance with smoking ban legislation, especially among youth and young adults frequenting bars. Moreover, it will promote tobacco prevention and cessation and will ultimately lead to a smoke-free generation.