INTRODUCTION

Though the national smoking prevalence has declined, nearly 34.3 million adults in the US still smoke cigarettes1. Moreover, use of alternative tobacco products (ATPs), such as little cigars/cigarillos (LCCs), smokeless tobacco, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), and hookah, has become increasingly prevalent. Notably, adolescence and young adulthood are pivotal times for tobacco uptake. Indeed, 22.3%, 9.1% and 4.8% of young adults reported use of cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco in 2017, respectively2. Additionally, in 2018, adolescent past 30-day use prevalence was 7.6% for cigarettes, 8.9% LCCs, 4.2% smokeless tobacco, 20.9% e-cigarettes, and 4.4% hookah3.

While the tobacco market has diversified, another relevant evolution in social norms and policy has occurred regarding marijuana, the most commonly used federally illicit drug3,4. In 2017, past-month use prevalence was 9.5% in adults, marking a 35% increase in the past decade4. In 2017, adolescent use demonstrated the first significant increase in 7 years, with 24% reporting past-year use and 6.5% past-month use3; while 2018 data indicate 22.2% past 30-day marijuana use prevalence among 12th graders4. Of note, the highest use prevalence is among those aged 18–25 years (21.5%, past-month use) with the 20s being a critical age period in marijuana use trajectories4.

Within this rapidly changing tobacco market and the evolving social norms regarding ATP and marijuana use, there is increased occurrence and concern of multiple product use across both tobacco and marijuana1,2, particularly for young people as earlier onset use has been associated with early onset of dependence4-6. Different tobacco products have potentially different nicotine levels; thus, multiple tobacco product use may be associated with increased risks of nicotine dependence7. Moreover, tobacco and marijuana use are highly correlated8. Popular combinations of substances used by young adults include co-occurring cigarette and e-cigarette use, cigarette and cigar use, and hookah, cigar, and marijuana use1,2,9.

As the landscape of tobacco and marijuana policies and social norms has evolved, trajectories of substance use have also changed. The ‘gateway’ theory, formulated originally to explain sequences in licit and illicit drug use, has been more recently applied to the range of tobacco products and marijuana10-12. Two major questions inherent in studying ‘gateway effects’ are: 1) ‘which products are used first?’, and 2) ‘what use profiles occur subsequently?’. In relation to the former, the 2012 Legacy Young Adult Cohort study of 4201 young adults found that 73% started with cigarettes first, 11% with cigars, 5% LCCs, 3% smokeless tobacco, and 4% hookah, with insufficient precision to report on e-cigarettes13. Additionally, 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey data indicated that 20.3% of middle school students and 7.2% of high school students reported using e-cigarettes as their first tobacco product14. A 2015 cross-sectional study of 3146 college students found that 38% chose cigarettes as their first product, 29% chose cigars, 6% smokeless tobacco, and 25% hookah (with no one reporting e-cigarettes as first product used)15. A 2013 study of New York undergraduate students reported that hookah was the first tobacco product used by 25.4% of ever tobacco users and 50% of never cigarette smokers16.

With regard to the second question, i.e. profiles of subsequent substance use, Suftin et al.15 found that those who initiated with cigarettes or cigar products were more likely to be current cigarette smokers compared to those who initiated with ATPs15. Other research has indicated that first using cigarettes increased the likelihood of initiating marijuana by four times17. Additionally, those who initiated with smokeless tobacco were twice more likely to initiate cigarettes and more likely to be dual or poly tobacco users15. Other studies have documented that experimenting with various products is related to increased risk for other substance use. For example, experimenting with e-cigarettes may increase risk of initiating cigarette use18,19, and experimenting with hookah may increase the risk of using combustible tobacco products and e-cigarettes20. In addition, e-cigarette or hookah use has been associated with higher risk of initiating marijuana use17. Moreover, marijuana use during adolescence and young adulthood is associated with increased risk of tobacco initiation21.

Cumulatively, the literature indicates some potential answers to the above questions. Specifically, it suggests that: 1) cigarettes are decreasingly the first products tried, 2) trying any single tobacco product increases the risk of trying other products, 3) profiles of subsequent use are likely different depending on which product was used first, and 4) subsequent product use risk may be specific to the first product used. However, this line of research is still limited and requires further examination.

The current study draws from a social developmental perspective22 that suggests that tobacco and marijuana use trajectories are shaped during adolescence and young adulthood by multilevel influences, including those at the individual, interpersonal, and community levels. Individual-level influences include sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, and other substance use. Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, data have indicated higher odds of using cigarettes first among those aged <17 years, females, Hispanics/Latinos, and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES), relative to their counterparts15,23. Cigars and LCCs as first products used have been associated with being male and younger at initiation15,24. Smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes as first products used are also associated with being male and White14. Choosing hookah as first product has been related to being female, Black, and higher SES15,16,23. Regarding marijuana, there is limited literature on prevalence and correlates of marijuana being first used; however, 2017 data indicate that 6.8% of adolescents had used marijuana before the age of 13 years25. In terms of use trajectories, smoking progression is greater among men and those with lower SES26. This research, although not inclusive of factors specific to trajectories of ATP and marijuana use, highlights sociodemographic differences in use trajectories to consider.

Regarding psychosocial factors, tobacco use and development of addiction have been associated with experiencing more adverse childhood events (ACEs), e.g. physical or sexual threat or abuse, parental divorce or separation27,28; as well as having higher depressive29 and ADHD symptoms29. While these associations have generally been found with cigarette smoking, research regarding these mental health concerns and use of ATPs is limited.

In addition to individual-level factors, interpersonal factors, such as parental tobacco and/or marijuana use, have been shown to impact on substance use trajectories4. Also, community-level influences on young adult tobacco use may include whether they live in rural or urban areas4,6, whether they pursue post-secondary education4,6, and the type of colleges/universities attended; for example, relative to four-year colleges/universities, community or technical colleges have higher student smoking prevalence30,31.

Thus, additional research is needed to fully characterize who is most likely to initiate use of distinct products and the subsequent use patterns relative to first product used. Thus, this study examined: 1) characteristics of young adults who initiate use of different tobacco products or marijuana; and 2) first product used relative to subsequent tobacco and marijuana use, specifically total number of products used in the lifetime, total number of products used currently, and current use of each product.

METHODS

This study analyzed data from a longitudinal cohort study (DECOY) that began in Fall 2014 with data collected every four months for two years (6 waves of data)31. Project DECOY was approved by the institutional review boards of Emory University, ICF, and the participating colleges/universities. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the research.

Participants and procedures

The parent study included 3418 students from seven campuses in Georgia, including two private universities, two public universities, one historically Black university (HBCU), and two community/technical colleges. Inclusion criteria were age 18–25 years and able to read English. Campus registrars provided lists of university email addresses for age-appropriate students. We randomly selected 3000 email addresses from each of the larger campuses and emailed a census of students at the campuses with ≤3000 age-appropriate students. Enrollment was conducted at each school separately and was staggered.

The total response rate for the study was 22.9% (N=3574/15607) and met the predetermined target sample size. Seven days after completing the baseline survey, participants were asked to confirm their participation via an email sent reiterating the parameters of the study. The confirmation rate was 95.6% (N=3418/3574). Compensation for participation was increased at every other survey wave to retain participants (i.e. $30 for the first two assessments, $40 for the third and fourth, and $50 for the fifth and sixth). Current analyses focus on participants who participated at Wave 6 (N=2403; 70.3% of baseline sample) and reported any lifetime use of any tobacco product or marijuana (N=1451; 60.4% of Wave 6 participants).

Measures

First product used

First product used was assessed at Wave 6 (Summer 2016) by asking: ‘For each of the following tobacco products, indicate the order in which you tried them in your lifetime’. Participants ranked the order of: cigarettes, large cigars, little cigars or cigarillos (LCCs), chewing tobacco, snus, e-cigarettes or vapes, hookah, marijuana, or chose ‘I have never tried any of these’. For analyses, large cigars and LCCs were grouped together as cigars, and chewing tobacco and snus were grouped as smokeless tobaqcco, thus yielding a total of 6 product categories (i.e. cigarettes, LCCs, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookah, marijuana).

Lifetime tobacco product or marijuana use

Total number of products ever used was assessed using the item: ‘For each of the following tobacco products, indicate the order in which you tried them in your lifetime’. This item was used to calculate total number of products ever used, which ranged from 1 to 6 in the analytic sample (as noted above).

Current tobacco product or marijuana use

Wave 6 tobacco product use was assessed by asking: ‘In the past 30 days, how many days have you: smoked cigarettes, cigars, little cigars, or cigarillos; used smokeless tobacco; used e-cigarettes; used hookah; used marijuana?’. Answer choices ranged from 0 to 30 days (participants had the option to refuse to answer marijuana-related assessments). The variable regarding the total number of products currently used (i.e. in the past 30 days) was created by summing the total number of products in the past 30 days, which ranged from 0 to 6 products currently used.

Sociodemographic measures

Sociodemographic characteristics, assessed at Wave 1, included age, sex, sexual orientation (heterosexual or sexual minority), race (White, Black, Asian, or Other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), and (as a proxy for socioeconomic status) parental education.

Setting

Setting was characterized by school type (i.e. private, public, technical college, or HBCU) and whether the school was in a rural or urban setting.

Psychosocial measures

ACEs were assessed at Wave 2 using a 10-item scale developed by the CDC32. ADHD symptomatology was assessed at Wave 2 utilizing the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Symptom Checklist (a 6-item scale)33. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.74. Depressive symptomatology was assessed at Wave 5 using the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 item (PHQ-9)34. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.87. Parental substance use was assessed at Wave 1 by asking: ‘Does any one of your parental figures use: cigarettes, cigars/cigarillos/little cigars, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, smoke tobacco using hookah or pipe, marijuana, or none of these (check all that apply)’.

Data analysis

Bivariate analysis was performed to examine the associations between participant characteristics (e.g. age, parental tobacco or marijuana use, ADHD symptoms) and first tobacco or marijuana product used (i.e. cigarettes, cigar products, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookah, marijuana), using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous variables. We then examined outcomes of number of products ever used (including the various tobacco products and marijuana) and number of products used in the past 30 days at Wave 6, first using bivariate analyses and then using multivariable linear regressions, respectively. Finally, we examined first product used in relation to each specific product used in the past 30 days, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial factors. In multivariable analyses, we used cigarettes as the reference group for the first product used variable. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v25.0 and significance set at alpha=0.05.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics and bivariate association between participant characteristics and first smoking product used at Wave 6 are presented in Table 1. Significant correlates of first product ever used included age, sex, race, parental education, school type (all p<0.001), rural/urban setting (p=0.002), ACEs (p<0.001), depressive symptoms (p=0.006), and parental use of cigarettes (p<0.001), ATPs (p=0.007), and marijuana (p=0.015).

Table 1

Participant characteristics and bivariate analyses examining first product used among ever users of tobacco and/or marijuana (N=1451)

Number of products ever used

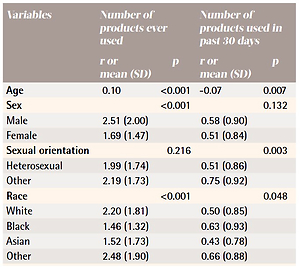

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) indicated that more products ever used was associated with choosing smokeless tobacco as first tobacco product (p<0.001), being older (p<0.001), male (p<0.001), ‘Other’ race (p<0.001), higher parental education (p=0.013), attending public school (p<0.001), living in an urban environment (p<0.001), more ACEs (p=0.001), more depressive symptoms (p=0.037), and parental use of ATPs (p=0.023) or marijuana (p=0.013).

Table 2. Bivariate analyses examining tobacco use outcomes in ever users of tobacco or marijuana (N=1451)

Multivariable regression analysis (Table 3) indicated that more products ever used was associated with cigarettes being the first product used (vs cigars, B=-0.66; e-cigarettes, OR=-1.33; hookah, B=-0.99; and marijuana, B=-1.05; p<0.001), as well as being older (B=0.06; p=0.012), male (B=-0.72; p<0.001) and White (vs Black, B=-0.30; or Asian, B=-0.60; p<0.05), more ACEs (B=0.07; p=0.011), and parental marijuana use (B=0.47; p=0.006). Adding the first product used to the regression model increased the R2 value from 0.107 to 0.176 (p<0.001; not shown in Tables).

Table 3. Multivariable analyses examining tobacco use outcomes in ever users of tobacco (N=1234) or marijuana (N=1308)

Number of products used in the past 30 days

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) indicated that more products used in the past 30 days was associated with smokeless tobacco as first product used (p=0.003), being younger (p=0.007), being a sexual minority (p=0.048), lower parental education (p=0.039), more ACEs (p=0.032), depressive symptoms (p=0.001), and ADHD symptoms (p=0.021), and having parents who use marijuana (p<0.001).

Multivariable regression analysis (Table 3) indicated that more products used in the past 30 days was associated with cigarettes being the first product used (vs cigars, B=-0.18; e-cigarettes, B=-0.37; and hookah, B=-0.18; p<0.05), as well as younger age (B=-0.04; p=0.003), being male (B=-0.15; p=0.006), more depressive symptoms (B=0.01; p=0.014), and parental marijuana use (B=0.40; p<0.001). Adding first product used to the regression model increased the R2 value from 0.035 to 0.044 (p<0.001; not shown in Tables).

Past 30-day use of each product

We also examined past 30-day use of each tobacco product and marijuana at Wave 6 to determine predictors of current use of each product, specifically focusing on first product used (using cigarettes as the reference group) as a predictor, controlling for all other covariates (results not shown in Tables).

Cigarettes

Predictors of past 30-day use of cigarettes (N=201; 13.9%) included first product used not being: cigars (OR=0.44; 95% CI: 0.27–0.72; p<0.001), e-cigarettes (OR=0.20; 95% CI: 0.06–0.67; p=0.009), hookah (OR=0.35; 95% CI: 0.18–0.69; p=0.002) or marijuana (OR=0.47; 95% CI: 0.30–0.75; p=0.001; Nagelkerke R2=0.128).

LCCs

Past 30-day use of LCCs (N=102; 7.0%) was predicted by first product used not being marijuana (OR=0.47; 95% CI: 0.24–0.92; p=0.027; Nagelkerke R2=0.176).

Smokeless tobacco

Past 30-day smokeless tobacco use (N=51; 3.5%) was predicted by first product used being smokeless tobacco (OR=4.32; 95% CI: 1.58–11.79; p=0.004; Nagelkerke R2=0.404).

E-cigarettes

Past 30-day e-cigarette use (N=79; 5.4%) was not significantly associated with first product used (Nagelkerke R2=0.081).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the extent to which first product used predicted subsequent use of tobacco and marijuana. In brief, study findings indicated that first using cigarettes (compared to other tobacco products or marijuana): 1) was most commonly reported, albeit followed relatively closely by marijuana and cigar products; and 2) predicted more products ever used in the lifetime and in the past 30 days. Moreover, there is some specificity in terms of first product use and current product use, particularly for cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and marijuana.

Of all the products, cigarettes (31.8%) were the most prevalent first tobacco product chosen, followed by marijuana (26.8%), cigars (21.8%), hookah (11.5%), e-cigarettes (4.2%), and smokeless tobacco (3.8%). This finding was consistent with prior research indicating that using cigarettes first was most commonly reported13,15. Additionally, our findings were consistent with previous research indicating that cigars and hookah were the second and the third most frequent first tobacco use choices13,15. Relative to the literature on cigarettes and ATPs, the literature on marijuana being the first product ever used is limited; however, prior research has indicated use prevalence of 6.5% among adolescents and 22.2% among 12th graders, indicating that there is the potential for a substantial proportion of users first using marijuana versus tobacco products3,4.

Not surprisingly, those who first used e-cigarettes were the youngest on average, with those first using cigarettes being the oldest, likely reflecting the different tobacco markets (i.e. cohort exposure effects) for those older versus younger during the periods in which they initiated. Those first using smokeless tobacco were disproportionately male and White, as prior literature would suggest14. Similarly, findings indicated that those first using hookah or marijuana were disproportionately Black, also supported by and reflecting the literature8. Those initiating with cigar products were more likely to have parents with more education. Those first using hookah were disproportionately represented by private college students whereas those who first used smokeless tobacco were highly represented by public college students; those first using cigarettes were disproportionately technical college students, and those from HBCUs disproportionately represented those first using marijuana. These findings reflect correlates of current use documented in the literature15,31. With regard to psychosocial correlates, those first using cigarettes had the highest number of ACEs and greatest depressive symptomatology on average, which reflects the established associations found in the literature, while the highest ADHD scores were among those who first used e-cigarettes or smokeless tobacco, which has not been robustly documented in the literature. Parental influence was also significant in that the proportion of participants with parents using cigarettes and ATPs was highest in those first using cigarettes; those who first used cigarettes or marijuana also had high proportions of parents who used marijuana. These findings suggest that parental influence may be relatively specific to the type of product use, which has been demonstrated previously4.

Regarding ‘gateway’ effects35, we documented a sequence of products used in relation to first product used. Results indicated that, compared to other tobacco products or marijuana, first using cigarettes predicted use of more products in the lifetime and in the past 30 days. Other research indicated that first using cigarettes or cigar products was associated with increased risk of being current cigarette smokers, compared to those who initiated with other tobacco products15. In addition, research has documented that first using cigarettes increased the risk of initiating marijuana use17. Thus, our current findings and those of others15,17 indicate that cigarettes pose a greater overall risk as an initially used product, relative to other tobacco and marijuana products. Also of note, there was no evidence that e-cigarettes lead to more products being used, which goes against findings from some longitudinal research suggesting e-cigarette use leads to smoking18,19, but supports other literature indicating that there is no ‘gateway’ effect associated with e-cigarettes12. While these findings contribute to the discourse regarding the population impact of e-cigarettes, these findings could be also due to the small sample cell counts, limiting power to detect the effects of initiating with e-cigarettes. Additionally, while this study documented that cigarette users used more products on average in their lifetime and in the past 30 days, there may have been some cigarette users that successfully reduced overall nicotine use or exposure, which was not captured in these analyses.

In addition, current findings indicated some specificity in terms of first product use and current product use. In particular, current use of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and marijuana, was highly specific to the first product used. These findings significantly contribute to the literature, as very little research has examined such specificity. However, one study by Sutfin et al.15 found that, in a sample of young adults, 65% of current smokers initiated with cigarettes, but 16.4% started with cigars, 11.1% with hookahs, and 5.7% with smokeless tobacco, indicating specificity in relation to cigarette use.

Additionally, current LCC use was associated with not using marijuana first, and current marijuana use was associated with not using hookah first. These findings are hard to interpret, particularly given the literature indicating that these three products are often used together9. This might reflect that, despite being commonly co-used, individual products are also used alone. For example, hookah has the least perceived risk in terms of its harm potential and addictiveness36, and thus may be used by those who have overall lower behavioral risk profiles.

With regard to sociodemographic factors, being male was a risk factor for using more products in the lifetime and in the past 30 days, while being White was also associated with using more products in the lifetime; these findings coincide with the literature regarding overall risk factors for use8,25. Being older was associated with total number of products ever use, but being younger was associated with total number of products used in the past 30 days, likely reflecting the fact that older participants had more time to experiment but that young participants were potentially in the midst of experimenting. In terms of psychosocial factors, experiencing more ACEs and parental marijuana use was associated with using more products in the lifetime, whereas greater depressive symptomatology was associated with using more products currently. These findings likely reflect the impact of early home life experiences on overall use risk behaviors27, but that current depressive symptomatology is the most critical indicator of current use risk29.

These findings have implications for research and practice. They suggest that the first tobacco or marijuana product used may be an indicator of subsequent use risk and that there is specificity in relation to use trajectories for some products. This is critical to note in both research and in addressing high-risk adolescents and young adults via anti-tobacco and anti-substance use interventions and health campaigns. Additional research is needed to better understand influences on initial product used and the impact of early substance use on subsequent use profiles, particularly using detailed and comprehensive data over time.

Limitations

Data were from colleges and universities in Georgia and thus findings may not be generalizable to all young adults in the US, particularly those not enrolled in college. However, the sample is diverse with regard to sex, race, ethnicity, and school location (urban vs rural), with the sample being largely representative of the sociodemographic characteristics of the student populations, albeit with less representation of men compared to women. The current study had a low response rate (albeit intentional and after meeting our target recruitment) and involved some attrition31. A particular limitation of this study was sample size, specifically with regard to small cell sizes for variables related to first use of smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, and hookah, as well as some correlates of interests (e.g. racial/ethnic minorities, sexual minorities). Additionally, despite the longitudinal nature of the parent study, these analyses focused on cross-sectional data from Wave 6 (Summer 2016) involving retrospective reports of first product used, which may be subject to recall bias, particularly for older young adults or those whose first use was some time ago. Relatedly, we did not assess age at first use of each product. Finally, the tobacco landscape (e.g. the tobacco market, social norms) was quite different in 2016 than it is now, limiting the implications of these data.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of cigarettes as the first product used predicted more products ever used in the lifetime and in the past 30 days, compared to most other products as first product used (excluding smokeless tobacco for both outcomes, and marijuana for past 30-day outcomes). Moreover, there is some specificity in terms of first product use and current product use, particularly for cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and marijuana. Thus, it is critical to intervene early upon substance use, particularly cigarette use, and to target specific subgroups at risk for progression. Moreover, public health campaigns should increase their efforts to address the risks and potential risks of ATPs and marijuana, as not doing so may lead to young people to more favorably perceive ATPs and marijuana, which may lead to use.