INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use and dependence is the leading cause of preventable premature death worldwide1, and it is a major cause of avoidable morbidity and mortality in the United States2. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), recent estimates indicate that there are more than 1 billion smokers throughout the world3,4, exposing billions of non-smokers to second-hand smoke (SHS)5. To date, the use of tobacco is responsible for the deaths of 6 million people each year4, including more than 600,000 non-tobacco users who die from SHS4. In 2004, it was found that 30% to 35% of adults and 40% of children were found to have been exposed to SHS5,6. Most of the disease burden of SHS, as measured by disability-adjusted life years, is experienced by children (61%), followed by women (24%) and men (16%)6,7. The proportion of deaths attributed to SHS is 47% in women, 28% in children, and 26% in men6,7. It is well documented that smoking is not only a health burden but also costs the world billions of dollars each year4.

The oral cavity is the first area of the body affected by tobacco products8,9. Tobacco use impacts many oral conditions, including dental caries, periodontal diseases, oral cancer, impaired wound healing, reduced ability to smell and taste, staining of the teeth, leukoplakia, oral precancerous lesions, halitosis and implant failure9–12. Tobacco-using patients have a 21% risk of crown and root caries, which is double that of previous users and never-users (10%)9. Furthermore, 20% of periodontal disease is attributed to tobacco use, and the severity of periodontal disease is directly related to the amount of tobacco used9. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, with an annual incidence of more than 500,000 cases, is another possible consequence of tobacco use, particularly if tobacco is chewed (smokeless tobacco use)13, 14. The oral cancer risk in smokers is 3.43 times higher than in non-tobacco-users, and the increase in risk is dose-dependent15, 16. The risk for oral cancer and periodontal disease of smokers returns to normal after ten years of smoking cessation15.

Saudi Arabia ranks 4th worldwide in the import of tobacco products17, 18. The WHO estimated the prevalence of smoking to be 17.1% among adults in 20154 and 14.9% of children and youth were found to be smokers in 201019. Because dental visits provide a unique base for successful tobacco use intervention, dentists, as health care providers, may play a significant role in the fight against tobacco use12. Previous studies have shown that oral health care providers are acutely cognizant of the negative impacts of tobacco use habits12.However, tobacco use intervention by dental care providers, compared to other health care providers, ranked the lowest, both in number and effectiveness worldwide10. Based on such findings, the WHO Global Oral Health Program recognized the implementation of tobacco use prevention and cessation (TUPAC) counseling guidelines to be of vital and essential importance in dentistry20. In March 2002, the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), during an ad-hoc Committee on Tobacco meeting, specified that the important role dentists and hygienists should play in tobacco use prevention should be highlighted21. This was further emphasized by the WHO, which stated that this tobacco use counseling should become an essential tenet of the dental curriculum22.

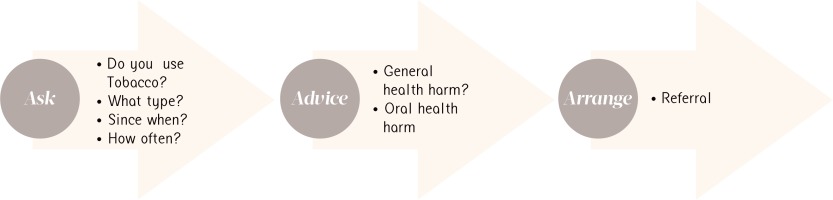

Various models of TUPAC have been adopted by the WHO, World Dental Federation, and the IADR23. They include the 3As (Figure 1), 4As, 5As, and 5Rs2,24. During the Second European Workshop on Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation for Oral Health Professionals held in Zagreb, Croatia in 2008, a consensus report on TUPAC was drafted, proposing four stages for tobacco use intervention15,24. Stage 1, Basic Care, included identification and documentation of patients’ tobacco habits in their medical records; Stage 2, Further Basic Care, consisted of brief intervention; Stage 3, Intermediate Care and Stage 4, Advanced Care, included more extensive intervention, including motivational interviewing15. These levels of approach give clinicians the freedom to offer tobacco counseling services that best suit them and their patients24. In this context, dental schools, as the primary source of education for dental professionals, should be viewed as the nucleus of effective tobacco-use intervention programs25.

METHODS

Patients attending KAUFD are registered and a dental record is created for each one. Dental Records have historically been paper-based and this has changed to electronic records in the past few years. In this study, the total number of dental records opened during the year was recorded and the sample size was determined using an online sample size calculator (Creative Research Systems®). This gave us the number of records to be sampled that would represent the total number opened during the year. Randomization of the sample was as follows: Sample “0” (S0) was the first dental record opened on January 1st 2013. A dental record was withdrawn every 10 dental records opened sequentially. Records were eligible only if the patient was aged 17 years or more. Maintaining a confidence level of 95% and a significance level of 5%, a minimum of 380 records would be representative for our study (http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm.). A final number of four hundred forty-nine dental records were included in this study.

An audit form was designed, which included:

Dental record number

Date the dental record was opened

Patient’s age and sex

Name/job description of the screening dentist

Tobacco-related information

Name of the treating dentist and his status (student, intern, faculty). Screening and treating dentists were classified as Student, Intern, General Practitioner (GP), or Faculty.

Audits were carried out in the Dental Records Office of KAUFD after working hours to avoid hampering the work flow of the institute (5pm until 8pm).

The tobacco information was audited to assess whether Stage 1, Basic Intervention, was carried out15, including asking and documenting the four questions of the 1st “A” (Ask) of the Basic Model, “AAR” (Figure 1). The four questions were: ‘Do you use any tobacco products?’; ‘What type of tobacco do you use?’; ‘Since when have you been using the tobacco products?’; and ‘How often do you use the tobacco product?’9 Three dentists carried out the auditing after calibration.

Data was entered, and analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 18 software. Descriptive summaries were completed for all items on the audit form. Further calculations were performed to correlate the questions asked with the clinician.

RESULTS

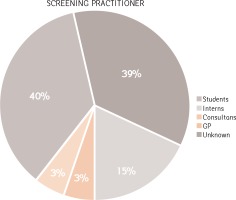

Of the 494 patients whose dental records were included, 44% were male (n = 217) and 66% females (n = 281). Age ranged from 17 years to 60 years (mean was 35.32 years). In addition, 191 (38.7%) of the patients were screened by students, 74 (15%) by interns, 15 (3%) by faculty members, and 14 (2.8%) by GPs. The screening clinician of the remaining 200 (40.5%) could not be identified (Figure 2).

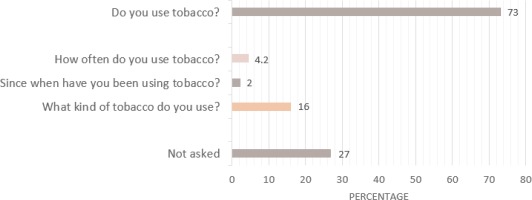

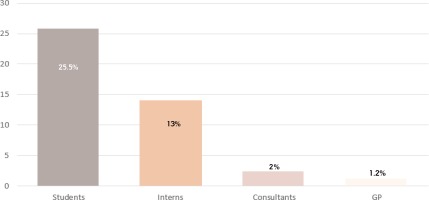

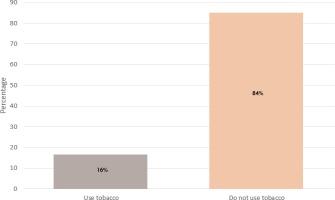

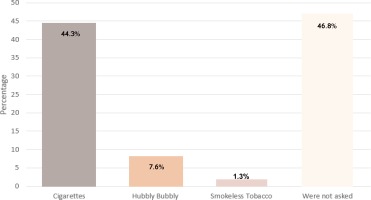

Three-hundred and sixty-four patients (73.7%) were asked whether they used tobacco (n tobacco-use = 364); however, of those asked, only 58 (16%) were further asked what type, 7 (2%) were asked since when, and 15 (4.2%) were asked how often (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 4, of the patients who were asked (n tobacco-use = 364), 93 (25.5%) were asked by students, 47 (13%) by interns, 7 (2%) by faculty members, and 4 (1.2%) by GPs. However, 213 (58.3%) of these records did not identify the practitioner who opened the file. The prevalence of tobacco use among those who were asked was 16% (n smokers =58) (Figure 5), of which 38 (66%) were between the ages of 18-45. Of those who were further asked what type, 26 (44.3%) answered “cigarettes” (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that most of the patients at KAUFD are asked whether they use tobacco or tobacco products (73.7%). However, further details about such use were not acquired from most of them. This finding reflects that most of our dental practitioners are indeed aware of their duty to inquire about tobacco habits as part of the ‘risk factors to oral health,’ but did not feel compelled to take it further than the first question. Dental students and interns were the most likely clinicians to ask about tobacco use (25.5% and 13%, respectively). This is similar to finding by Uti and Sofola (2011) who found that students were more likely than dentists to ask their patients about their tobacco use habits26. In a study conducted in a single dental school in the UK, 94% of the students did record their patients’ tobacco habits in their charts16. In the US, the percentage of dentists who ask their patients is much lower, between 30% and 50%10,11,25. It was surprising that faculty members showed less responsibility than their students in this regard, but a conclusive statement cannot be made, because 40% of the records failed to identify the screening dentist. However, the conclusion that among the 40%, the likely screening dentists were staff and not students can be made because all students working on cases must provide proof that the patient was being treated by them. This makes the signing of their name and personal identification number a mandatory step in the education process.

Overall, however, the practice of tobacco use history-taking among all practitioners is low. This is alarming, because studies have shown that health care providers are more likely to provide tobacco use intervention when they indicate their patients’ habits on their charts25.

In our study, we found that two-thirds (66%) of the tobacco users ranged between the ages of 18 and 45 years. This agrees with previous evidence suggesting that most smokers visit dental offices at an early age, during which intervention may significantly affect the long-term occurrence of tobacco-use comorbidities10, 24. The available data has shown that the dental team is in a favorable position for such intervention10,15,27,28. More than 50% of smokers make annual visits to their dentists and are usually seen by the same dentist, which increases the opportunity for establishing a positive rapport between dentist and patient10–12,16,24,29. Because the effects of tobacco, such as aesthetic alteration, are more evident in the oral cavity than in other systems, it is more sensible that the dental office is the focus for effective tobacco use intervention practices8,10. Despite the fact that more advanced intervention has been proven to be more effective24, evidence has shown that even basic intervention with simple advice from any health care provider results in small but significant tobacco use cessation rates1,8,24,30.

Our finding that 16% of Saudi patients attending KAUFD during that period were users of tobacco (smoked) agrees with the estimate by the WHO (17.1%)19. This makes it of paramount importance that further education and establishment of tobacco use intervention protocols be taught and applied. Our work has revealed that KAUFD is not diligent enough in this practice, and this could be the result of a lack of proper knowledge and training. Reports have shown that more than half of the US and less than two-thirds of the European dental schools provide tobacco-use intervention program courses11, and various methods of training highly improve the tobacco cessation intervention outcomes31.

The results presented here have provided a fundamental insight during the implementation of the new electronic health record system (EHR-R4) in the school. Medical history and risk assessment in the EHR-R4 are presented in the form of a check-list. It was suggested, and subsequently implemented, that the software require that either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ be indicated for each question at the time of history taking. A second audit of the electronic health records will provide insight into whether the practice of tobacco use history is carried out more frequently than when paper-based records are used.

Currently, Saudi Arabia has a total of sixteen dental schools; six of them are private, and the rest are governmental32. The results of this study cannot be generalized for all undergraduate dental programs in Saudi Arabia but does necessitate further investigations to include the majority of the dental schools nation-wide. The implementation of TUPAC by dental practitioners is not yet a fundamental parameter of competent dental practices in Saudi Arabia. Further education and implementation of, at the very least, Stage 1 basic intervention, is highly recommended; this would undoubtedly improve the service we provide our patients.

CONCLUSION

The education of dental graduates is one of the tenets in the fight against tobacco. It is not enough to teach students the didactic part of tobacco use prevention and cessation, but it is also important to ensure the continue the practice. As an educational institute, we have the ability to ensure this practice by integrating TUPAC in the curriculum and assigning to it the grading weight for the completion of clinical cases. However, without continuous monitoring, this will remain at best a sporadic practice particularly among non-students practicing in the dental school. Therefore, audits, which measure particular key performance indicators (KPIs) such as the implementation of TUPAC by all staff, can be used to evaluate the excellence of the institute in its commitment to benefiting the community.