INTRODUCTION

The transgender population is considered a minority within the sexual and gender minority (SGM) groups, and they face greater challenges than those who self-identify as lesbian, men having sex with men, or bisexual individuals1. ‘Transgender’ describes a person whose sense of gender does not correspond with their assigned gender at birth2. Female-to-male (FTM) transgender individuals were assigned female at birth but personally identify themselves as male, and male-to-female (MTF) transgender individuals were assigned male at birth but personally identify themselves as female. Transgender individuals may under-utilize healthcare resources due to discrimination, stigma, and difficulty of finding healthcare providers who are knowledgeable about the physical and mental health issues affecting the transgender population3-6.

Tobacco use is a major contributing factor to morbidity and mortality worldwide7, and previous research has shown that smoking rates are higher among sexual and gender minority (SGM) groups8-11. Stress, internalized homophobia, normalization of smoking behavior, and targeted advertising by the tobacco industry, are just some of the multiple risk factors contributing to the increased smoking rate among SGM individuals12,13. Also to consider is the dynamic between gender role attitudes and smoking, which has not only shifted social norms and diversified smoking patterns14-16, but has influenced smoking cessation outcomes17,18. In the general population, there is evidence indicating that men are more likely than women to engage in a variety of risky behaviors, including smoking, alcohol use, and avoidance of health screenings, to project a more masculine image of themselves19,20. Even among gay men, prior research has found that individuals who want to portray a more masculine image are more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as tobacco use, alcohol use, and illicit drugs12,20-22.

While most of the published literature evaluates cigarette smoking among lesbians, men having sex with men (MSM), and bisexual adults, research on smoking among transgender populations is limited. Two national representative studies conducted among transgender adults in the US indicate a smoking prevalence ranging from 27.2%23 to 35.5%2. However, these important efforts failed at examining intragroup differences in smoking patterns within the transgender population (FTM vs MTF). To our knowledge, only one recent publication based on secondary analysis of data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study has addressed tobacco use behaviors among 154 transgender individuals2, reporting 40.1% and 30.9% smoking prevalence among FTM and MTF transgender individuals, respectively. However, the difference in smoking prevalence in these two groups was not statistically significant.

To investigate whether there are differences in terms of smoking behavioral patterns based on gender identity in this vulnerable group, we studied the prevalence of smoking and potential determinants of smoking risk among a sample of transgender individuals in Houston, Texas.

METHODS

Design and data collection

Our convenience sample included transgender adults (aged ≥18 years) attending the 2015 Houston Pride Festival, as well as transgender patients seeking care at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic. Respondents provided information regarding age, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex at birth, racial/ethnic background, health insurance coverage, educational level, working status, and tobacco use behaviors (e.g. consumption of cigarettes and other tobacco products, use of electronic nicotine-delivery systems, intention to quit, cessation resources used). However, our analysis was restricted to cigarette smoking as only 16.5% of the individuals reported using tobacco products other than cigarettes. Items in the survey used simple checkboxes or Likert-type rating scales with skip patterns when appropriate. No remuneration of any kind was given to participants. This study was approved by the institutional review board at MD Anderson Cancer Center (Protocol PA14-0350).

Outcomes

Our survey included a question about gender identity with several categories such as male, MTF transgender, female, FTM transgender, not sure, and other; but only those respondents self-identified as transgender individuals (either MTF or FTM) were included in the analysis.

Our analysis plan for this particular report was centred on cigarette smoking (main outcome). Therefore, all participants who responded ‘Yes’ to the questions: ‘Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes (5 packs) in your entire life?’ and ‘Do you now smoke every day or some days?’, were classified as current smokers. Respondents who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but who had quit smoking at the time of survey completion were classified as former smokers. Never smokers were respondents who had never smoked, or who had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

Covariates

Age was self-reported as a continuous variable. Although more detailed data regarding race/ethnic background were available (Non-Hispanic Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, and other), ethnicity was dichotomized as White vs Non-White, given the relatively small sample size of the other racial/ethnic groups in our study. We classified level of education in two mutually exclusive groups: High school or less vs Higher than high school. Employment status was recoded into working full-time or part-time vs not working or volunteering. Healthcare coverage was categorized as Insured and Uninsured. Self-report of being diagnosed with anxiety and/or depression indicated history of psychological distress (Yes/No).

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared test (or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate) was used to compare categorical variables between the two subgroups (FTM vs MTF). For comparing continuous variables two-sample t-test was used. Gender identity was used to predict current smoking status using logistic regression, adjusting for sociodemographic determinants such as age, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, health insurance coverage, and psychological distress diagnosis. Since diagnosis of depression and anxiety disorders (psychological distress diagnosis) have been strongly associated with smoking behavior in the scientific literature24, this variable was also included in the model. We did not conduct any variable selection, such as stepwise selection, because such approaches are known to lead to biased coefficient estimation25. The significance threshold was set at 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata v. 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

In all, 132 transgender individuals completed the survey. The mean age of the participants was 32 years (SD=11.7 years). Of these, 72 individuals (54.5%) self-identified as MTF and 60 identified as FTM (45.5%). The sample group was racially and ethnically diverse: 45.8% Caucasian, 25.2% Hispanic/Latino, 16.8% African American, and 12.2% reported other racial/ethnic background. Most of the transgender individuals were single (62.9%), not living with children in their household (83.6%), and with an educational level higher than high school (77.3%). Full-time or part-time employment was reported by 72.8% of the sample, while 28.5% had no healthcare coverage. More than a third of the respondents (38.6%) reported having a diagnosis of psychological distress such as depression and/or anxiety disorders. More details and statistically significance differences between the transgender subgroups are given in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the study sample (N=132)

| Characteristics | Categories | Total N=132a n (%) | MTF n=72 n (%) | FTM n=60 n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 31.8 (±11.71) | 33.8 (±12.91) | 29.5 (±9.73) | 0.038b | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Lesbian | 13 (10.2) | 9 (12.9) | 4 (7.0) | ||

| Gay | 7 (5.5) | 5 (7.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0.068c | |

| Bisexual | 19 (15.0) | 15 (21.4) | 4 (7.0) | ||

| Queer/other | 62 (48.8) | 29 (41.4) | 33 (57.9) | ||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 26 (20.5) | 12 (17.1) | 14 (24.6) | ||

| Sex assigned at birth | |||||

| Male | 64 (49.6) | 64 (90.1) | 0 | ||

| Female | 63 (48.8) | 5 (7.0) | 58 (100.0) | NA | |

| Intersex | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | ||

| Racial/ethnic background | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 60 (45.8) | 41 (56.9) | 19 (32.2) | ||

| African American | 22 (16.8) | 5 (6.9) | 17 (28.8) | 0.003d | |

| Hispanic | 33 (25.2) | 17 (23.6) | 16 (27.1) | ||

| Othere | 16 (12.2) | 9 (12.5) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| Living status | |||||

| Single | 78 (62.9) | 46 (69.7) | 32 (55.2) | 0.036c | |

| Married or living with significant other | 38 (30.6) | 14 (21.2) | 24 (41.4) | ||

| Otherf | 8 (6.5) | 6 (9.1) | 2 (3.4) | ||

| Living with children | |||||

| Yes | 21 (16.4) | 10 (14.7) | 11 (18.3) | 0.58d | |

| No | 107 (83.6) | 58 (85.3) | 49 (81.7) | ||

| Level of education | |||||

| Higher than high school | 99 (77.3) | 52 (76.5) | 47 (78.3) | 0.802d | |

| High school or less | 29 (22.7) | 16 (23.5) | 13 (21.7) | ||

| Work status | |||||

| Working full-time or part-time | 91 (72.8) | 39 (59.1) | 52 (88.1) | <0.001d | |

| Not working/volunteer | 34 (27.2) | 27 (40.9) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| Healthcare coverage | |||||

| Insured | 93 (71.5) | 45 (64.3) | 48 (80.0) | ||

| Uninsuredg | 37 (28.5) | 25 (35.7) | 12 (20.0) | 0.048d | |

| Psychological distressh | |||||

| No | 81 (61.4) | 43 (59.7) | 38 (63.3) | ||

| Yes | 51 (38.6) | 29 (40.3) | 22 (36.7) | 0.671d | |

a Due to missing data not all the variables add up to the total sample (N=132): Five cases missed response on sexual orientation, 3 on sex assigned at birth, 1 on race/ethnicity, 8 on living status, 4 on living with children, 4 on education level, 7 on employment status, and 2 on health care coverage.

Prevalence rates and predictors of current cigarette smoking

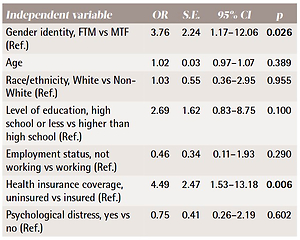

Prevalence of current cigarette smoking was 13.9% among MTF and 26.7% among FTM transgender individuals. The number of cases in the regression model was reduced to 120 due to missing data. Results of the logistic regression that modeled current cigarette smoking in association with gender identity (main predictor) adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and other risk factors such as age, gender identity, race/ethnicity, level of education, psychological distress, employment status, and health insurance coverage, showed that compared to MTF transgender individuals, FTM participants were significantly more likely to be current smokers (OR=3.76; 95% CI: 1.17–12.06; p=0.026). Uninsured participants were also significantly more likely to be current smokers than those who were insured (OR=4.49; 95% CI: 1.53–13.18; p=0.006) (Table 2).

Table 2

Factors associated with current cigarette smoking among transgender adults (n=120)

DISCUSSION

Our finding among 132 surveyed transgender adults was that FTM individuals were over 3 times more likely to report being current cigarette smokers compared to MTF transgender adults, facing a higher burden of health morbidity and mortality associated with cigarette smoking. Compatible with our findings, the only other study in the scientific literature comparing subgroups of transgender individuals found that FTM transgender adults had significantly higher rates of past 3-month tobacco use (47.8%) compared to MTF transgender individuals (36.1%)26. Our study also found that individuals who lacked health insurance coverage were over 4 times more likely to report being a current cigarette smoker compared with those who had health insurance coverage. This issue is particularly concerning because lack of healthcare access also limits access to smoking cessation services and resources27,28.

Our findings build on the literature assessing tobacco use among the SGM population, but with a focus on transgender smokers. Our research also goes one step further by addressing disparities within the transgender population (MTF vs FTM).

Strengths and limitations

Since the study was conducted with a convenient sample from Houston, it may not be generalizable to other regions in the State of Texas or nationwide. However, our study sample of 132 transgender individuals is of relevance if we consider that two studies based on nationally representative samples have included 16829 and 1542 self-identified transgender individuals. Also, prevalence of cigarette smoking could be underestimated due to selection bias, as some of the study participants were recruited from a health clinic serving the local transgender population. Since this is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to observe differences in smoking initiation and intention to quit between MTF and FTM transgender individuals over time. However, transitioning is an ongoing process, not an event, that can take several months, years or even a lifetime. We also acknowledge that the wider the confidence interval in the reported odds ratios, the greater the uncertainty associated with our estimates. Despite these limitations, this study reports on important findings by examining intragroup differences in smoking behavior among the transgender population.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study addressed a critical knowledge gap by expanding on smoking-related disparities that exist within the subgroups of transgender adults. However, more research is needed for tailoring smoking cessation for transgender subgroups and achieving a better understanding of their needs to successfully quit smoking. Further research is also needed to assess on a large scale the teachable moments during the process of gender transition when the promotion and implementation of smoking cessation interventions could be more effective.