INTRODUCTION

Smoking is a well-known major cause of early preventable mortality and morbidity. About 6 million people die worldwide every year due to smoking-related diseases, and it is expected that tobacco will kill as many as 1 billion people this century unless WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is implemented1. In 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control introduced MPOWER policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic2. Turkey fully implemented the MPOWER package of World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. As a means of offering help to quit tobacco, a smoking cessation quitline (Hello 171) was established, which provides consultancy services to those who want to quit smoking and register in smoking cessation clinics such as in the Cancer Early Detection, Screening and Training Centers (KETEMs), and in state and university hospitals across Turkey3. The present study took place in another establishment also providing smoking cessation services, a tertiary hospital in Ankara.

To develop and implement more effective tobacco control measures, the assessment of the association between sociodemographic factors and smoking cessation is crucial. Maintenance of smoke-free status is as important as smoking cessation itself in preventing smoking-related morbidity and mortality.

The aim of this study was to investigate the sociodemographic, clinical and smoking-related factors that may be associated with long-term abstinence (>36 months smoking cessation) in subjects attending a specialized smoking-cessation clinic.

METHODS

Recruitment

The study was conducted in adults aged 18–65 years who were either referred, because of their comorbid conditions, or who applied voluntarily, to a smoking cessation clinic of tertiary care services in Ankara, Turkey, between January and December 2011. Subjects were not included in the study if their sociodemographic, employment, environmental, health characteristics, smoking-related and clinical data were not completely available in the hospital records. The study sample did not include patients with major psychiatric affects such as psychoses, as they were followed in a different clinic for psychiatric disorders. Subjects who were willing to participate in the study and gave information about their smoking status three years after participating in the smoking cessation program were involved in the study.

Hospital files of 530 subjects could be reached from a total of 840 subjects followed in the smoking-cessation clinic between the specified dates. These subjects were contacted by phone and 261 agreed to volunteer for the study. The study was approved by Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (297/2014).

Assessment of sociodemographic, employment, environmental, smoking-related, health and clinical characteristics

The subjects’ sociodemographic data (age, gender, education level, marital and childbearing status), employment status, household smoking, smoking-related parameters (age of smoking initiation and cumulative amount of smoking), health characteristics (psychiatric illness history, comorbid systemic illness) and clinical characteristics (level of nicotine dependence, level anxiety and clinical assessment of mood) were obtained from the patients’ files. Subjects had been prescribed varenicline, bupropion, or bupropion together with nicotine replacement treatment according to their clinical assessment in the smoking-cessation program. None of the subjects received only nicotine-replacement therapy. Medications used by the patients within the smoking-cessation program were free-of-charge. The choice of smoking cessation treatment and clinical follow-up regarding frequency of visits, were also noted from the hospital files.

The age of smoking initiation was evaluated in three age groups: <16, 16–22, and >22 years. The cumulative amount of smoking was calculated as pack-years by multiplying the number of years of smoking by the number of packs smoked per day. Level of nicotine dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND): ‘low or very low’ (0–4), ‘moderate’ (5), and ‘high or very high’ (6–10), on a 10-point scale. Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-21) and Beck’s Anxiety Inventory (BAI) were used to assess subjects’ emotional states. The subjects’ level of depression was categorized based on their BDI-21 score: ‘absence of or mild mood disturbance’ (≤16), ‘borderline clinical or moderate depression’ (17–30), and ‘severe or very severe depression’ (≥31). The subjects’ level of anxiety was graded according to their BAI score: ‘minimal’ (0–7), ‘mild’ (8–15), ‘moderate’ (16–25), and ‘severe’ (26–63).

Assessment of the smoking status of subjects

The smoking status of the subjects at three years follow-up after participating in the smoking-cessation program was assessed through telephone interview. Smokers who participated in the smoking-cessation program in 2011 were called by phone to assess their smoking status three years after participating in the program. Subjects were questioned about their smoking status based on three parameters: 1) if they had quit for at least three months after participating in the program; 2) whether they restarted smoking after successfully quitting for at least three months and if so, the duration they maintained their quit status; and 3) their smoking status three years after participating in the program. Accordingly, subjects were divided into five groups depending on the months they remained abstinent after admission to the program: <3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and >36 months.

Outcome measures

Sociodemographic, employment, household smoking, smoking related, health and clinical characteristics of subjects who never quit smoking and subjects having quit for three months or more were compared to assess the factors that contributed to the success of a quit attempt. Subject characteristics were compared to determine which factors may have affected the duration of smoking abstinence after participating in the smoking-cessation program, these included: sociodemographic, employment, environmental, smoking-related, health and clinical characteristics of subjects who refrained from smoking for <3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and >36 months. Subsequently, in order to determine the factors that affect long-term smoking cessation, the same analyses were performed between subjects abstinent and not abstinent for >36 months.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables (age, age of smoking initiation, cumulative amount of smoking, and number of follow-up visits) were grouped into categories and were transformed into categorical variables. All variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. For comparison of subjects with different smoking cessation periods, chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used. All statistical tests were two-sided and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences)® version 22.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic, employment, household smoking, smoking-related and health characteristics of the study subjects are presented in. Assessment of the clinical characteristics of the subjects is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1

Sociodemographic, employment, environmental, smoking-related and health characteristics of the study population (N=261)

Table 2

Clinical characteristics of the study population (N=261)

Among study subjects, pharmaceutical intervention was planned with varenicline in 150 (57.5%), bupropion in 85 (32.6%) or bupropion together with nicotine replacement treatment in 26 (10.0%) subjects, according to their clinical assessment. Upon admission to the smoking cessation program, follow-up visits were scheduled as 4–6 visits for the first 3 months, two visits on the 6th and 12th month, and additional visits any time according to the patient’s needs.

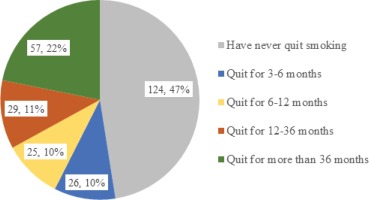

Of 261 study subjects, 124 (47.5%) had never quit smoking, 26 subjects (10.0%) had stopped smoking for 3–6 months, 25 subjects (9.6%) had stopped smoking for 6–12 months, 29 subjects (11.1%) had stopped smoking for 12–36 months, and 57 subjects (21.8%) had stopped smoking for more than 3 years (Figure 1).

Parameters that significantly differed between the subjects that quit and not quit smoking for at least 3 months were marital status (p=0.007), childbearing status (p=0.03), household smoking (p=0.001), FTND score (p=0.03), level of anxiety (p=0.04), and number of follow-up visits within the smoking-cessation program (p<0.001). The rates of being single, not having children, presence of other smokers in the household, high or very high nicotine dependency, and moderate–severe anxiety, were higher among subjects who never quit smoking (Table 3).

Table 3

Parameters significantly different between subjects who never quit smoking and subjects having quit for at least 3 months

Comparison of sociodemographic, employment, household smoking, smoking-related, health and clinical characteristics between subjects who refrained from smoking for <3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36 and >36 months, revealed that marital status (p=0.002), childbearing status (p=0.049), household smoking (p=0.001), educational level (p=0.02), mood encountered by BDI-21 (p=0.02) and number of follow-up visits (p<0.001), were significantly different. Whereas age (p=0.27), gender (p=0.87), occupation (p=0.46), level of nicotine dependency assessed by Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependency (p=0.07), level of anxiety assessed by BAI (p=0.16), age of smoking initiation (p=0.20), cumulative amount of smoking (p=0.50), presence of comorbid illness (p=0.80), psychiatric illness history (p=0.10), and medications used for smoking cessation (p=0.61), were not significantly different between the five groups (Table 4).

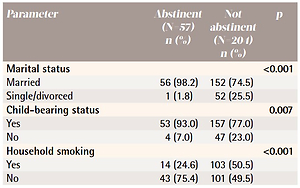

Parameters that significantly differed between subjects who were abstinent and not abstinent for >36 months were marital status (p<0.001), childbearing status (p=0.007), household smoking (p<0.001), age of smoking initiation (p=0.02), psychiatric illness history (p=0.01), and number of follow-up visits (p<0.001) (Table 5).

Table 4

Parameters significantly different between subjects grouped according to duration (months) of smoking abstinence

Table 5

Parameters significantly different between subjects having and not having quit for more than 36 months

DISCUSSION

The present study is important in revealing factors influencing smoking cessation and maintaining quit status in smokers who voluntarily participated in a smoking-cessation program. Frequency of being married, having a child, and absence of household smoking-cessation program. Frequency of being married, having a child, and absence of household smoking, were significantly higher both in subjects who were able to quit smoking for at least 3 months and in those who were able to maintain their quit status for more than 3 years. Also, low or moderate level of nicotine dependence and minimal–mild levels of anxiety were significantly more frequent in subjects who were able to quit smoking for at least 3 months. Parameters significantly different between subjects having and not having quit for more than 3 years were age of smoking initiation and psychiatric disorder history.

Smoking cessation interventions are important components of MPOWER policy as means of offering help to smokers to quit tobacco use. Smoking cessation rates are reported as 16–22% with behavioral therapy4, 15–25% with nicotine replacement treatment5,6, 28.8–44.2% with bupropion7, and 23–29.7% with varenicline8. The rate of success in quitting cigarette smoking after attempting a smoking-cessation program also depends on demographic factors such as age, level of education, marital status, household smoking, and work conditions9. In 2011, the Turkish Ministry of Health supported a smoking-cessation treatment program that provided coverage of medication expenditures for treatment of nicotine dependence for smokers who were willing to quit. The smoking cessation success rate of this program was reported to be 28.0% at follow-up at one year. Smoking cessation rates were higher in the elderly, females, participants with lower Fagerström scores, those with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular events, and if medication for nicotine dependence was used for more than 3 months. Significant factors found to be related to the maintenance of smoking cessation for 12 months were: longer duration of medical intervention for smoking cessation, absence of COPD and absence of cancer, in the same study10. Differently from the report published by Çelik et al.10, which included subjects who were admitted to primary, secondary and tertiary health-care facilities in Turkey, the subjects in the present study were followed in a single smoking cessation clinic in a tertiary hospital in Ankara. Moreover, the smoking cessation rates were evaluated at follow-up at 3 years.

For the maintenance of tobacco control interventions regarding smoking-related mortality and morbidity, the long-term cessation in the population of smokers is at least as important as successful quitting. Approximately 65 per cent of all quitters relapsed in the first 3 months, with 10 per cent more relapsing from 3 to 6 months after quitting, and an additional 3 per cent relapsing between 6 months and one year following a quit attempt11.

Determining the factors that influence long-term smoking cessation is important since it may enable to identify subjects who are at high risk of failure to maintain quit status, and to design individualized treatment strategies and follow-up. Previous studies have reported older age, being married, high educational level, low levels of daily cigarette consumption, initiation of smoking after the age of 20 years, and absence of other smokers in the household as other factors related to higher quit rates12-14, while older age, high educational level, low prior tobacco consumption, high social status and absence of other smokers in household were predictors of long-term smoking cessation15,16.

This study reveals that family and housing circumstances, as well as smoking-related and mental health characteristics of subjects, influence maintenance of smoking cessation. Maintenance of quit status for more than 36 months was as low as 1.8% among subjects who were single or divorced, and 7% among subjects without children. Smoking cessation rate over 36 months was found to decrease to about half in the presence of other smokers in the household. Marital status, childbearing status and household smoking were factors affecting successful quit after a cessation attempt and maintenance of abstinence. Although some study results reveal that male gender is related to higher quit rates and is a predictor of long-term smoking cessation, gender difference is not related to effectiveness of smoking-cessation treatment in real-world assessments17. In the present study gender was not found to be related to smoking cessation rate over 36 months following a smoking-cessation program.

Clinical evaluation of mood in subjects who attended the smoking-cessation program is critical because the presence of depressive symptoms assessed with BDI-21 are related to lower rates of abstinence. According to study results, subjects with clinical depression (BDI-21 ≥17) had lower rates of maintenance of quit status. Moreover, none of the subjects with severe and extreme depression (BDI-21 score ≥31) had refrained from smoking for more than 12 months. Similarly, age of smoking initiation is also a significant factor that should be considered in follow-up of subjects in smoking-cessation programs. Smoking cessation rate for 36 months was higher among subjects who started smoking after 22 years of age and lower in subjects who started smoking before 16 years of age.

Psychiatric illness history was another parameter important for abstinence. In the present study, the rate of refraining from smoking for more than 36 months in subjects with psychiatric illness history was half that of those without a history of illness. Smoking cessation interventions in smokers with psychiatric disorders is a public health problem. Smoking patterns and smoking cessation interventions have some unique features in these subjects18. Smoking is even more prevalent among people with psychiatric illness and they suffer greater morbidity and mortality from smoking19. Smoking prevalence is twice as high among depressive subjects20. In a population-based study, smoking prevalence ranged from 34.3% to 59.1% in adults with mental illness or serious psychological distress compared with 18.3% in adults with no such illness21. The neurobiological association between smoking behavior and psychological disorders has also been shown22. People with psychiatric disorders are more nicotine-dependent and quit smoking at lower rates compared to the general population. Successful smoking cessation rates were reported to be lower in individuals with mental illnesses compared to those without this condition, 26–45% versus 54%, respectively21.

The number of follow-up visits subjects attended within the smoking-cessation program was significantly different between subjects who were or were not able to quit smoking for at least three months, and between subjects with different smoking cessation periods. This finding highlights the importance of follow-up visits and close follow-up in smoking cessation interventions. Accordingly, follow-up visits should be encouraged, especially in subjects who are not likely to refrain from smoking after quitting. In order to maintain quit status, follow-up should be extended to 3 years or more according to clinical evaluations based on whether subjects: are single, have no children, have other smokers in the household, started smoking at an early age, have a history of psychiatric illness, have high BDI-21 scores.

Limitations and strengths

In this study, information on subjects’ smoking status and their smoking cessation duration relied on self-reports to determine smoking status instead of verification by measurement of exhaled CO levels. Since the number of follow-up visits subjects attended within the smoking-cessation program was significantly different between subjects with different smoking cessation duration, it is concluded that follow-up visits help in maintaining smoking cessation. However, this finding might be because those continuing cessation will come for follow-up visits, while the others drop out. Also, all subjects that were followed in the smoking-cessation clinic between the specified dates were not included in the study due to missing data in the hospital files of some subjects and that some of the patients refused to participate in the study. The study sample did not include patients with major psychiatric affects such as psychoses as they were followed in a different clinic for psychiatric disorders. The major strength of the present study is that it evaluates smoking cessation success over 3 years.

CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that family and housing circumstances, as well as smoking-related and mental health characteristics of subjects, influence maintenance of smoking cessation. The study presents long-term smoking cessation rates in smokers who are self-motivated to quit and highlights the influence of clinical and demographic features on the continuation of smoking abstinence, from a follow-up at 3 years. Determination of demographical and clinical factors influencing long-term smoking cessation rates may enable to identify subjects who have high-risk of failure to maintain quit status, and to individualize treatment strategies and follow-up.