INTRODUCTION

Tobacco consumption represents an important public health problem, including in the European region, which still has a high level of smoking prevalence (29%)1. To address tobacco use comprehensively, the World Health Organization (WHO)1 proposed policy objectives through the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) treaty2, including monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies, protecting people from tobacco smoke, offering help to quit smoking, warning about the dangers of tobacco, enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and raising tobacco taxes (MPOWER)3. To ensure adequate implementation and enforcement of the treaty, it is important that groups in civil society continuously put tobacco control on national policy agendas4. A previous cross-country study suggested that the way advocacy groups are organized may be an important factor in this4.

Scholars use various terms to describe advocacy groups in civil society. For example, in English the following words are used: ‘consortia’, ‘coalitions’, ‘alliances’, and ‘partnerships’5, which all refer to organizational arrangements in which organizations or individuals in civil society work together to reach communal policy goals5,6. For the remainder of this article we use the term ‘partnership’ to refer to such arrangements.

Efforts to advance tobacco control are typically counteracted by the tobacco industry7,8. Industry involvement in tobacco control policymaking is seen as a major obstacle in the formulation of comprehensive tobacco control policies2,9. Research into industry ‘interference’ with tobacco control policy examined industry lobby tactics and conduct7,10. This has resulted, for example, in the Policy Dystopia Model9, and the Tobacco Control Interference Index11.

However, much less attention has been devoted to the organization of tobacco control advocacy partnerships. The literature on this topic is dominated by single country case studies which describe the development of tobacco control policies within a country over time and the role of partnerships therein, focusing on objectives, roles, activities, and (framing) strategies of tobacco control partnerships12-16. However, such studies do not explicitly focus on the partnership characteristics which may increase the likelihood that national tobacco control objectives are met. A better understanding of partnership capacity would enable existing and future tobacco control partnerships to be more influential.

A health advocacy network is more effective when it has capable, well-connected and widely respected leaders, when there is a governing structure capable of bringing together a diversity of actors, and when it is able to resolve disputes among partnership members and organize collective action17. Partnership networks are more likely to be effective if their members know how they can frame policy issues in such a way that they resonate with society and politicians. These factors are in line with the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) Theory, which identifies similar conditions for success of advocacy organizations: having the right allies, having shared resources, and being able to develop a common strategy18.

Lasker et al.19 proposed a widely cited model of concrete characteristics associated with the capacity of partnerships active within the field of health promotion. They posit that there are four broad categories. The first refers to resources, which include money, space, equipment and goods, skills and expertise, information, connections to people, organizations and groups, endorsements, and convening power. The second category refers to member characteristics, notably heterogeneity (variation in types of members) and level of involvement. The third describes the relationships among partners, referring to trust, respect, conflict, and power differentials. The fourth category refers to characteristics of the partnership as a whole. These are leadership, administration and management, governance, and efficiency.

The aim of this paper was to provide an overview of the characteristics of tobacco control partnerships across Europe, using the framework of Lasker et al.19 on partnership capacity.

METHODS

Likely determinants of partnership capacity

First, we organized a convenience panel group of tobacco control experts from 10 European countries (one expert per country) during the European Network on Smoking Prevention (ENSP) congress in Madrid, June 2018. The panel members were tobacco control advocacy experts with extensive experience in tobacco control in their respective countries. They were mostly non-governmental (NGO) leaders and had typically been active in tobacco control policy advocacy for several decades. The experts were from the following countries: Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, and Sweden.

The experts identified key characteristics related to the success of their national advocacy efforts in the field of tobacco control, first in subgroups presenting their country experiences, followed by a plenary discussion. In the plenary session, we sought to reach consensus on the most relevant partnership characteristics in tobacco control policy advocacy. A certain degree of data saturation was observed, as the raised characteristics per subgroup were highly comparable. To preserve an open discussion, we did not employ or mention the framework of Lasker et al.19 during the subgroup discussions and the plenary panel.

Ten characteristics emerged, and all fitted well within the Lasker et al.19 framework: 1) financial independence from government; 2) expertise to interpret and transform data and to engage in advocacy; 3) an evidence based approach; 4) access to nationally relevant data; 5) connections to policymakers, journalists, researchers, and other partnerships; 6) partner heterogeneity; 7) conflict resolution; 8) a central coordinating office; 9) clear rules or statutes; and 10) a shared vision/consensus.

Development of a measurement tool

As a second step, we developed an English language 22-item English language tool based on the insights of the expert panel and the framework. Additional insights from the literature were also taken into account5,19,20. In an iterative process, various rounds of feedback and discussions among the authors were needed to develop a draft of the tool.

The tool distinguishes three dimensions corresponding to three categories of Lasker et al.19: resources of the partnership (12 items), member characteristics (2 items), and organizational characteristics (8 items). A fourth category, ‘Relationships among partners’, had one single item (conflict resolution). We felt that the ability to resolve conflicts can also be considered an organizational aspect, so we decided to put this one item under ‘organizational characteristics’. An overview of all items of the tool can be found in Table 1. The complete tool with answer categories, further clarifications of terms, and scores can be found in the Supplement file.

Table 1

Partnership characteristics relevant to tobacco control partnership capacity

Pilot testing

We conducted two pilot tests to make the tool practically administrable to tobacco control partnerships across Europe. We carried out the first pilot test at the Dutch Alliance for a Smoke free Society (Alliantie Nederland Rookvrij). Two employees concerned with political advocacy filled in the tool separately and provided written feedback on items they felt were ambiguous or unclear. The tool was discussed per item and amended accordingly. In some cases, items were slightly rewritten to make them more concrete or (most often) a note of clarification was added. For example, the item ‘The partnership includes professional communication experts (yes/no)’ was complemented with a note explaining ‘Professional communication experts are professionals which are formally trained (i.e. received education) in the field of communication and/or who have ample experience in this field’(see Supplementary file for the tool ).

The second test consisted of sending an online version of the tool to international tobacco control advocacy experts recruited by an employee of the European Network for Smoking and Tobacco Prevention (ENSP). Seven of nine approached experts filled in the tool and provided feedback on items. We asked them to report any items: 1) which were not formulated sufficiently understandable, 2) were formulated ambiguously, 3) that they were unable to answer with the information that they had, and 4) they felt missed certain topics. This feedback led to several additional amendments, mostly adding more clarification notes (Supplementary file).

Most amendments concerned the precise clarification and delineation of the meaning of terms (e.g. ‘Structural funding’ was more precisely defined as ‘funding on a weekly/monthly/yearly basis, as opposed to incidental funding for one or a few specific projects’). Furthermore, various experts requested a clear definition of ‘partnership’. We then defined a partnership as ‘a group of people and/or organizations who coordinate their efforts during a long-term with the aim of fostering tobacco control policies at the national level’, based on a definition by Winer and Ray21.

Selection of respondents

We set out to identify existing tobacco control partnerships in all countries of the European Union. To this end, in the fall of 2019, ENSP approached 77 tobacco control advocates across 30 European countries through ENSP’s tobacco control advocacy network. ENSP sent an initial e-mail invitation to complete the tool, followed up by a first and second reminder. Respondents from five countries did not answer to the invitation and the reminders (Austria, Croatia, France, Hungary, and Latvia). Respondents from Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, and Slovakia stated that there was no national tobacco control partnership in their country. A total of 25 respondents filled in the tool for 25 partnerships across these 20 European countries (with 2 partnerships in Spain, 2 in Greece, and 4 in Italy).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We formulated additional inclusion and exclusion criteria for analysis. We decided that a partnership should consist of at least two organizations (i.e. no single organization), be based in civil society (i.e. be non-governmental), and should not be restricted to scientific organizations only (i.e. no scientific or epistemic communities). These additional criteria led to the exclusion of partnerships in three countries: Estonia (1 governmental organization), Italy (3 scientific communities and 1 single organization), and Greece (2 single organizations).

In summary, of all 25 countries that responded to our invitation, five countries did not have a partnership according to the answers of respondents and three countries did not have a partnership according to our definition and inclusion criteria. We analyzed and compared 18 partnerships across 17 countries (there were two partnerships in Spain).

Assigning scores

We applied scores to each answer category for each item in the tool (see Supplemental file for the scores per item). We allocated a higher score to answer categories that contribute to partnership capacity. For example, if the answer to the question about whether the partnership includes professional scientists was ‘yes’ a score of 1 was assigned, and ‘0’ if the answer was ‘no’. We did not attempt to assign relative weights to items, since there was no empirical evidence on which to base decisions about which characteristics are more important than others in relation to partnership capacity.

The allocation of scores to the answer categories led to a maximum total score of 18 for the resources dimension, 19 for the member characteristics dimension, and 8 for the organizational characteristics dimension. To make the dimensions mutually comparable, we divided the scores per dimension by the maximum dimension score (which resulted in a maximum score of 1 per dimension). In the presentation of the comparison between the 18 European partnerships, we anonymized the partnerships by assigning a random identification number.

RESULTS

Statistical analysis

Resources

The resources dimension (including working relationships) consists of 12 items (items 1–12, Table 1). Table 2 summarizes the results for this dimension. Of all 18 partnerships, 15 did not receive structural funding from the government. Concerning expertise, 15 partnerships included scientists and 15 included communication experts. Thirteen partnerships included professional, trained tobacco control lobbyists. All partnerships indicated that they work completely or partly in an evidence informed manner, which means that their messages and policy proposals are informed by scientific evidence. All 18 partnerships had access to information about the national context concerning smoking prevalence and trends, while only 11 partnerships had access to information on tobacco industry presence and lobbying. Half of partnerships had at least some influence on the research agenda of scientific organizations which fund or carry out research. Most partnerships maintained working relationships with civil servants (17 out of 18 partnerships, with contacts at least once every three months). Less partnerships maintained working relationships with the Minister of Health or Secretary of State (11 out of 18 partnerships, with contacts at least once per 12 months).

Table 2

Resources of the 18 European tobacco control partnerships

Member characteristics

The member characteristics dimension consists of 2 items (items 13–14, Table 1).

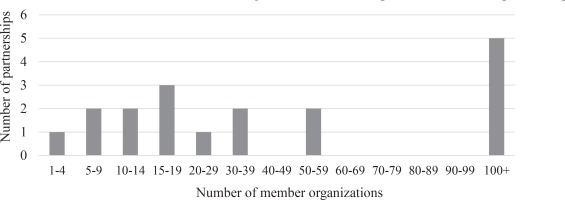

Table 3 shows the types of members that were included in the partnerships. All 18 partnerships included medical organizations, yet only 4 out of 18 partnerships included commercial companies, such as pharmaceutical companies. The total number of partnership member organizations is depicted in Figure 1. Of all 18 partnerships, 8 included less than twenty member organizations. Five partnerships included more than 100 member organizations.

Organizational characteristics

The organizational characteristics dimension consists of 8 items (items 15–22, Table 1). Results can be seen in Table 4. Thirteen out of 18 partnerships had agreement on the roles and responsibilities of member organizations (7 partnerships had agreement, 6 had some agreement). Twelve partnerships had an agreement on how credits are divided across member organizations (3 partnerships had agreement, 9 had some agreement). Such credits may refer to public recognition of expertise and authority of individual members, their contributed efforts, and their public visibility. Of all 18 partnerships, 12 indicated having a leadership figure who connects, inspires and resolves conflicts within the partnership. Concerning strategy, 17 out of 18 partnerships had an agreement on common goals (11 partnerships had agreement on a common goal, 6 had some agreement) and 16 partnerships had agreement on a common strategy (9 partnerships had agreement, 7 had some agreement). Furthermore, 16 out of 18 partnerships were able to formulate a shared public position on tobacco issues (14 partnerships were able, 2 partnerships were more or less able). Lastly, 16 partnerships were able to avoid or resolve conflicts between member organizations (6 partnerships were always able, 10 partnerships were usually able).

Table 4

Organizational characteristics of the 18 European tobacco control partnerships

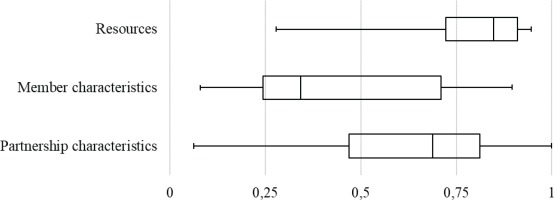

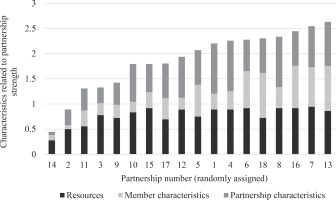

Comparison of prevalence of characteristics across partnerships

As can be seen in Figure 2, there was variance across European partnerships with regard to the prevalence of characteristics related to partnership capacity. With a maximum score of 3, the lowest scoring partnership (No. 14) scored 0.45 and the highest 2.63 (No. 13). The majority of countries were in the range 1.4–2.4. Figure 3 shows the dispersion of total partnership scores per dimension using boxplots. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were 0.19 (IQR: 0.72– 0.91) for resources, 0.47 (IQR: 0.24–0.71) for member characteristics, and 0.34 (IQR: 0.47–0.81) for organizational characteristics.

Figure 2

A comparison of prevalence of characteristics related to tobacco control partnership strength across 18 European partnerships

Finally, we calculated correlations between the dimensions. Member characteristics had moderately strong correlation with resources (r=0.47) and organizational characteristics (r=0.43). The correlation between resources and organizational characteristics was strongest (r=0.79).

DISCUSSION

European tobacco control partnerships differ substantially concerning the prevalence of characteristics related to their potential capacity to advance national tobacco control. Those partnerships that scored highest on partnership strength had a balanced distribution across the three dimensions of partnership characteristics. The relatively low total scores on the member characteristics dimension suggests that European partnerships may gain most by increasing the volume and heterogeneity of its associated members. While most partnerships scored relatively high on the organizational characteristics dimension, room for improvement can still be found, particularly in reaching agreement on roles and responsibilities and agreement on the adequate division of credits among member organizations. On a more positive note, European partnerships scored relatively high on the resources dimension, suggesting there is considerable expertise, ample access to national information and good connectivity to policymakers, journalists and to other partnerships.

Most European partnerships were found to have scientists and communication experts among its members, while 13 of 18 partnerships included professional lobbyists. The American Cancer Society emphasizes the importance of professional lobbyists for advocacy in tobacco control partnerships or coalitions22. Such lobbyists may be hired, or existing employees may be trained to acquire such skills.

A considerable number of partnerships have access to various types of national level research data relevant for tobacco control advocacy. However, there was room for improvement concerning access to data on tobacco industry presence and lobbying, as five partnerships did not have access to this type of information. Respondents from half of the partnerships indicated they had some influence on setting the research agenda of national organizations that fund or carry out tobacco control research. Other partnerships may invest more in relationships with academia (e.g. universities or statistical offices), to get access to national research data.

Almost all partnerships maintained working relationships with civil servants (17 of 18 partnerships) and Members of Parliament (16 of 18 partnerships), and some had also access to the Health Minister or to a Secretary of State (11 from 18 partnerships). It is noteworthy that working relationships with civil servants are thus widespread. Civil servants may offer the most effective route of influence, as they are more likely to remain in office when there is a regime change, compared to ministers or members of parliament23, and they may play important insider roles in advancing tobacco control24.

Five partnerships had not come to an agreement regarding roles and responsibilities of member organizations, and 6 partnerships had not agreed on how credits are best divided between member organizations. Previous research suggests that in order to be most productive, partnerships must have clear membership roles and responsibilities5. Furthermore, inadequate division of credits could lead to a discontinuation of a partnership, when individual organizations seek to draw public recognition at the expense of others. To increase productivity and to prevent discontinuation, it may be important to reach agreement in such areas. A strong leader could play a connecting role. However, 6 out of 18 partnerships in our study indicated that they did not have such a leadership person.

A noteworthy finding was that 5 out of 18 partnerships had more than 100 formal partners. This may perhaps be explained by a different strategy of some partnerships compared to others. Some partnerships may want to demonstrate a broad public support base25. Alternatively, it could be that such large partnerships gathered momentum over time and therefore many organizations elected to join voluntarily (i.e. a so-called ‘bandwagon effect’)22,26. In contrast, some partnerships may prefer a small number of member organizations, as this may facilitate reaching consensus and speedy decisionmaking processes. The critical issue may not be the overall size of the partnership per se, but whether the specific mix of member organizations and the ways in which they participate help to achieve communal goals19.

Our tobacco control partnership tool assumes a specific model of collaboration, in which a partnership consists of various organizations pursuing a common goal (reducing smoking prevalence) and a specific way of reaching that goal (political advocacy). In this model, according to Lasker et al.19, more resources, more members, more heterogeneity, and greater agreement on issues is presumed to result in a stronger partnership and more influence. However, it can be questioned whether there is such a ‘one size fits all’ model for effective political advocacy, given the fact that countries have unique tobacco control policy environments4,16,27. For example, the scientific or epistemic communities in Italy, although, excluded from our study as they did not meet our definition of an advocacy partnership, are recognized as authorities in the national tobacco control policy debate and therefore play prominent roles in defining the problem and proposing viable policy solutions28.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that we aimed to assess large corporate-style national partnerships. The tool that we developed was thus designed to assess national level professional partnership organizations which are likely to be research-informed, to have a network which includes national government officials and which have the resources to employ professional lobbyists. The study did not focus on small grassroots type of advocacy initiatives prevalent in many countries, for example from medical doctors, which have been particularly effective in some countries in getting tobacco control issues on the societal and political agenda. Sometimes, such initiatives are incorporated in larger national-level partnership or they may function as an effective outsider group, such as in the Netherlands16.

Another limitation of the tool is that it did not assess overall financial resources of partnerships, only whether funding is dependent on government funding. Several partnerships reported not receiving funding from the government or not having an office. But we do not know how well they are funded, for example by health charities or other sources. Funding is necessary to pay for professional lobbyists, executive officers and an office. Future studies may gather more information on the sources and amount of funding, and how civil society could be more engaged in raising funding.

There are a few methodological caveats to the tool presented in this study. Firstly, the validity of the tool remains to be determined. Even though the positive and relatively strong correlations between the dimensions suggest that they measure dimensions of the same construct, we do not know whether it indeed measures the construct ‘partnership capacity’ in terms of being effective in advancing tobacco control. We suggest that future research examines the predictive validity of the tool and its subdimensions. Secondly, having one respondent filling in the tool per national partnership may have introduced some level of measurement error due to subjectivity. A point of improvement in further research may therefore be to apply different assessment strategies, for example consensus meetings with a few members of each national partnership, by involving two or more independent respondents per country to improve inter-rater reliability, or have several members of the partnership respond to the tool and compare results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was the first to assess tobacco control partnerships’ capacity across Europe. We showed that tobacco control partnerships vary greatly in the extent to which they possess specific characteristics associated with their ability to advance tobacco control. There is much room for improvement of European tobacco control partnerships. The measurement tool may function as a practical starting point for tobacco control advocates who wish to improve the capacity of their partnerships and may inspire future research in this field.